This Week's Deity

Profile

AIDHS

(Hades, King of the Dead) |

How to identify him: It's tough. He's invisible! But if you meet him, you'll know it.

|

The background of the table above is a field of asphodel flowers.

Images

of Hades and Persephone are available courtesy of Laurel Bowman at the University of Victoria

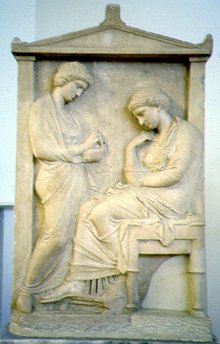

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description of

Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage, he doesn't

have an active role in any myths because he's too busy to leave his kingdom. The only time

he did was to claim his bride, Persephonê, who is his partner in everything. Even in

sculptures and paintings you almost never see him without Persephonê at his side.

The bas relief sculpture to the left is featured in our textbook; for

further information about what the details mean, see page 238.

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description of

Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage, he doesn't

have an active role in any myths because he's too busy to leave his kingdom. The only time

he did was to claim his bride, Persephonê, who is his partner in everything. Even in

sculptures and paintings you almost never see him without Persephonê at his side.

The bas relief sculpture to the left is featured in our textbook; for

further information about what the details mean, see page 238.

Hades' wife is far more active than he. Even when Odysseus descends to the underworld and has

some unpleasant experiences there, notice he keeps suggesting that it's Persephonê,

not Hades, who is tormenting him. Hades himself is just a little too scary to be mentioned

out loud. Therefore a number of euphemisms have sprung up around his name. As well as

the ones mentioned by Powell on page 282, Polydegmôn ("receiver of many") and

Polyxenos ("host to many"), Hades was sometimes called Zeus Katachthonius, or

"the underground Zeus."

It might be easier to understand Hades' role if you think of him in terms of that last title.

As Zeus is the keeper of order among the living, Hades is the keeper of order among the dead.

He is not death itself--the Greeks had a separate god for that, named Thanatos--but

rather the ruler over departed souls. He is extremely fair and just, so much so that he is

unbending, unforgiving, and utterly inflexible. He's not an evil individual by any means,

but he's sort of like that irritating

person at work who always quotes from the rule book and refuses to deviate an inch from

standard procedure. You know they're right, but that doesn't make it easier to accept.

Here's another common misunderstanding: in fact, Hades' realm does not have exactly the same

name as its ruler in the original Greek, though it's frequently translated that way. Greek is an

inflected language, which means a word takes on different endings to indicate its grammatical

function. When his name is used to refer to the underworld, it is invariably used in the

possessive--Hades' or of Hades. So the phrase Go to Hades' would have

the same grammatical structure as Eat at Joe's. The underworld is named after its

ruler in the same way that Joe's is named after its owner. You don't call a restaurant

Joe, and an ancient Greek didn't call the underworld Hades.

As Pluton, Hades is the god of wealth--and indeed, the materialistic Romans took

take "Pluto" as his given name. This is because of his underground home, the source of

mineral wealth in the form of gold and gems and agricultural wealth in the form of crops

(which explains his relationship with Persephonê).

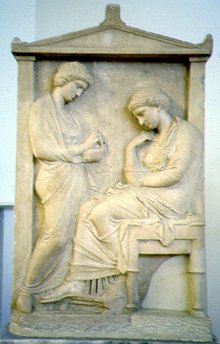

As Powell mentions on page 283, weapons and jewelry were frequently buried with

a corpse in order to keep its ghost at rest and prove the survivors were not receiving too

much benefit from a relative's death. It was also common for wealthy women's grave markers,

like the one on the right, to portray the deceased's jewelry box. The box is usually held by

a slave as the mistress chooses her favorite ornament.

As Powell mentions on page 283, weapons and jewelry were frequently buried with

a corpse in order to keep its ghost at rest and prove the survivors were not receiving too

much benefit from a relative's death. It was also common for wealthy women's grave markers,

like the one on the right, to portray the deceased's jewelry box. The box is usually held by

a slave as the mistress chooses her favorite ornament.

This is not an indicator of the belief that "you can take it with you." It's quite the

opposite. There is a significant difference between the gloomy classical idea of the

afterlife and that of their more optimistic neighbors, the Egyptians, who enjoyed their time on

earth so much they couldn't conceive of an eternity that wouldn't be similar to their everyday

lives. Egyptian tombs were packed full of grave goods because they believed that their dearly

departed might need them in the next world. Greek and Roman tombs were packed with the

same to keep a jealous ghost from haunting the survivors.

For the same reason, noisy and extravagant mourning was considered appropriate. If you were

worried that your own family wouldn't be able to put on a noisy enough show, you could always

hire professional mourners who were guaranteed to scare off any errant ghosts who hadn't yet

found their way to their final destination.

Ghosts were also supposed to roam the earth on moonless nights, which is why Hades is closely

associated with the goddess Hecatê.

Hecatê was a goddess of boundaries and crossroads and the dark of the moon; the Romans

associated her with the more terrifying side of wild, untameable Diana.

|

Lemur from Madagascar

The Romans also had a name for ghosts, lemures. I know that sounds funny today--we

can't help thinking of those odd little creatures from Madagascar--but the Roman name came

first. The animals were given the name by classically-educated explorers because of their

nocturnal habits, eerie silence, and bug-eyed appearance...not to mention the fact that the

local folk tradition claimed that they housed the souls of the dead.

One way of keeping a ghost from walking was to pin its feet together, as was sometimes done

with exposed infants. Powell mentions the case of Oedipus, who suffered this fate and was

maimed for life as a result. The name "Oedipus" is a pun that reflects on Oedipus's nature

("know-it-all") and on his physical characteristics ("twisted foot").

The Topography of Hades' Realm

Accounts vary about where Hades' kingdom is located. In some cases it's under the earth, and

in others, such as in the Odyssey, it's at the western edge of the world, in the land

of the Cimmerians. The Cimmerians were a real people who lived near the Black Sea--north of

Medea's home in Colchis. It's Medea's aunt, Circe, who gives Odysseus directions on how to get

there. Both Medea and Circe are described repeatedly in mythology as devotees of Hecatê.

Do you begin to see a pattern here?

Archaeological evidence

seems to point to a possible connection between the entrance used by Odysseus and a subterranean

temple complex perched above the Acheron River in northwestern Greece. Yes, the Acheron is a

real river. It's the one that is usually seen as the outside boundary of the underworld. Its

name means "sorrowful." The other three rivers associated with Hades' kingdom, the Styx

("hateful"), Pyriphlegathon ("flaming with fire"), and Lethe (river of forgetfulness, from

which our word "lethal" is derived), are wholly mythical.

Perhaps one of the reasons the Styx is so hateful is it's the river the gods swear by when

they need to make a particularly binding oath. Once they've sworn by the Styx, they cannot

go back on their word or even use their typical trick of trying to weasel around it.

Traditionally, the spirits drink from Lethe so they will be able to bear the loss of their

life above ground. Plato changes this a bit in his myth of Er (see page 293), where he

introduces the idea of reincarnation and claims that they drink to forget their previous life

and begin afresh. Homer doesn't mention Lethe. His gloomy ghosts have to continue in their

shadowy existence with full knowledge of what they have lost.

Acheron is not the only boundary.

Sometimes Lake Avernus, near Naples, is described as the portal to the underworld. This Italian

alternative, of course,

is the route that the Roman hero Aeneas takes on his journey. Other accounts say that

there is an entrance to the underworld through a bottomless lake at Lerna on the Peloponnesus

(the place where Heracles killed the hydra), and that that's how Dionysus retrieved his mother

from the land of the dead. According to Pausanias 2.36.1, Lerna is

the point where Hades rose out of the ground to abduct Persephonê.

Sometimes the ancient writers mention a place called Erebus, which is either the final

destination of the dead or a place that they pass through. If it's their final destination,

Tartarus is depicted as a separate area, circled by Pyriphlegathon, where punishment is doled

out to those who offended the gods. If it's a place they pass through, everybody winds up in

Tartarus but it's divided up into better and less desirable neighborhoods.

The meadows of

asphodel are located either in Erebus or in Tartarus--wherever the spirits wind up. Despite

the rather pleasant name, don't confuse the asphodel meadows with the Elysian fields. Asphodel is a ghostly-looking flowering weed. The fields of Elysium are a riotous paradise of every

pleasant plant you can think of. The only problem is, nobody knows exactly where these fields

are. Some authors locate them somewhere out in the sea, on the "Islands of the Blessed," which means we might conceivably be able to get there! In the second century A.D., the satirist Lucian wrote about just such a possibility in his True

History. A boatload of sailors who have been blown off-course wind up on these islands

and meet the Homeric heroes. Odysseus is bored to death and wishing he could go off on

another voyage, so he smuggles out a message to the sea-nymph Calypso with the help of the

story's narrator. Menelaus runs up against a familiar situation when his wife Helen runs

away with one of the sailors.

|

Dante and Virgil in trouble

(Eugene Delacroix, 1822)

Those spirits who are not bound for Elysium or the Islands of the Blessed have to cross a river (either Acheron or Styx) in the boat of

the ferryman Charon. To pay the ferryman, a person would be buried with a coin under his or

her tongue. Without that fare, the spirit would suffer the same fate as those who were

improperly buried and would be required to wander aimlessly on the far bank of the river for

a hundred years.

According to some sources, Charon's boat is made out of horses' hooves, the only material that

can resist destruction in the corrosive waters of the Styx. Horses' hooves are a very light

substance, but then an insubstantial spirit doesn't weight much. As Powell tells us, the human

bodies of Aeneas and the Cumean Sibyl nearly sink the boat, and the same thing almost happens

again in Dante's Inferno when Dante and Virgil climb on board.

The planet Pluto's solitary moon is named Charon. Even though this satellite wasn't discovered

until 1978, the tradition of giving mythological names to heavenly objects continues.

The most thorough description of Hades' realm is given by Virgil, which is not really surprising.

The Aeneid, like the Argonautica, is primarily a literary epic that was written by

the author rather than an oral epic composed on the fly, like the Homeric works. Because of this

distinction, such poems tend to be a little more elaborate.

For a spectacular illustrated voyage through Virgil's vision of Hades' realm, visit the

University of Virginia's tour of Aeneas in the Underworld.

Or you might want to look at Carlos Parada's map of the underworld, which

charts the progress of both Odysseus and Aeneas. It's a little slow to load, but it's really

worth seeing. Don't miss the material below the map, which is also quite good. Parada also

offers an exhaustive (10 pages on my printer) annotated rundown on the underworld and afterlife.

To read more about Hades, click here

and here

for entries from the Encyclopedia

Mythica and Perseus, and

here for an overview of myths about

Hades in capsule form, courtesy of Carlos Parada's Greek

Mythology Link.

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description of

Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage, he doesn't

have an active role in any myths because he's too busy to leave his kingdom. The only time

he did was to claim his bride, Persephonê, who is his partner in everything. Even in

sculptures and paintings you almost never see him without Persephonê at his side.

The bas relief sculpture to the left is featured in our textbook; for

further information about what the details mean, see page 238.

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description of

Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage, he doesn't

have an active role in any myths because he's too busy to leave his kingdom. The only time

he did was to claim his bride, Persephonê, who is his partner in everything. Even in

sculptures and paintings you almost never see him without Persephonê at his side.

The bas relief sculpture to the left is featured in our textbook; for

further information about what the details mean, see page 238. As Powell mentions on page 283, weapons and jewelry were frequently buried with

a corpse in order to keep its ghost at rest and prove the survivors were not receiving too

much benefit from a relative's death. It was also common for wealthy women's grave markers,

like the one on the right, to portray the deceased's jewelry box. The box is usually held by

a slave as the mistress chooses her favorite ornament.

As Powell mentions on page 283, weapons and jewelry were frequently buried with

a corpse in order to keep its ghost at rest and prove the survivors were not receiving too

much benefit from a relative's death. It was also common for wealthy women's grave markers,

like the one on the right, to portray the deceased's jewelry box. The box is usually held by

a slave as the mistress chooses her favorite ornament.