Study Guide

Study Guide

Satyricon

Study Guide

Study Guide

Satyricon

The image to the right, furnished courtesy of Maecenas: Images of Ancient Greece and Rome, is from the "House of the Tragic Poet" at Pompeii. Cave Canem means "Beware of the Dog" in Latin. We don't know if it was simply a popular theme, or if Petronius actually saw this very same mosaic floor and recreated it as a frightening fresco on Trimalchio's wall.

About the Satyricon

One of the earliest novels in the world, Petronius's Satyricon is a fascinating glimpse at what ancient Rome was really like. Satire was a uniquely Roman invention--in fact, the only literary form wholly invented by the Romans rather than adapted from Greek originals--and Petronius was particularly well known for it. I guess you'd have to have a sense of humor if your job was to be the arbiter of taste at the court of the Emperor Nero.

I've asked you to read this selection because it is so uniquely Roman; there is nothing like it in Greek literature. The story is very loosely (emphasis on "very") based on Homer's Odyssey, in that the hero goes through a number of adventures on land and sea and is persecuted by a god. In the Satyricon, however, the god who pursues the hapless Encolpius is Priapus, who has cursed him with impotence because of something he did to disturb the secret rites of a randy priestess named Quartilla in Priapus's grove. Unfortunately the text is very fragmentary so we don't know exactly what he did, but some people have come up with theories. Whatever it was, Priapus really didn't like it.

"Dinner with Trimalchio" is the longest fragment that exists of the original work.

At the baths

The name Agamemnon means "leader of men," which might be more appropriate if it weren't for the fact that this particular Agamemnon and his sidekick Menelaus are a couple of charlatans. How the mighty have fallen!

In footnote 7 it says that Trimalchio claims the two clumsy slaves are pouring a libation (by the way, Falernian was the most expensive wine available in ancient Rome and nobody would be likely to spill it carelessly--or, even less likely, give some to his slaves). One pours out a libation to a god, never to a human being.

Trimalchio is breaking a sumptuary law by wrapping himself in "thick scarlet felt" (1094). Scarlet clothing was reserved for noblemen and members of the royal family, and purple (the color you'll see him using on the borders of his napkins at dinner) for the royal family alone.

Trimalchio's entryway

Just as one didn't pour out libations to human beings, one didn't put frescoes of one's own life story on one's walls. Trimalchio's choice of divine patrons is interesting: Minerva is the strategist and schemer, while Mercury is the protector of thieves and businessmen. So in effect he shows that he has risen on the strength of his own talents and cunning--a point he belabors again and again in the ensuing conversation.

Isn't it great that he includes the price tags in the picture of the slave market? It reminds me of the old phrase about the person who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

When Encolpius asks the porter about some other pictures on the wall, he's told that they represent "the Iliad, and Odyssey, and the gladiatorial show given by Laenas" (1095). This casual confusion of the epic heroes with contemporary gladiators might come as something of a shock if you expect Trimalchio to revere the ancient stories. Remember, though, that we are no longer in classical Greece, but in crass, commercial Rome at the time of Nero. Homer died about eight centuries ago, and anyway he's a Greek...we know how the average Roman felt about the Greeks from the way Ulysses and Sinon are depicted in the Aeneid.

Educated boys would study Homer at school, in the same way that we study Shakespeare in high school, but Trimalchio wasn't an educated boy and he isn't an educated man. He's a freedman, a person who started off as a slave and eventually worked his way up to a point where he could buy his freedom. Although he did learn accounting (1094), Homer and other classic works of literature probably were not a part of his curriculum, despite the fact he now has "two libraries, one Greek, one Latin" (1101).

The dining room

You might want to look at this description or this reconstruction of an ancient Roman dining room, or triclinium, to get an idea of what this place might have looked like. Because of its social function, the triclinium was often the most elaborate and largest room in the public part of a Roman house. Trimalchio, who always has to overdo everything, has no fewer than four triclinia (1109)!

Trimalchio breaks two more sumptuary laws here: the aforementioned napkin, and the gold rings on his fingers. These rings were not supposed to be worn by anybody below the equestrian class, which is considerably above his touch.

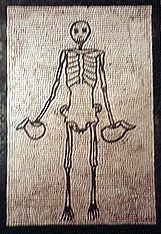

Trimalchio's obsession with death and the

silver skeleton that is brought out to the table is not as weird as it might sound. This

preoccupation seems to have been reasonably normal; the image to the left, another ancient Roman

mosaic, once graced somebody's floor.

Trimalchio's obsession with death and the

silver skeleton that is brought out to the table is not as weird as it might sound. This

preoccupation seems to have been reasonably normal; the image to the left, another ancient Roman

mosaic, once graced somebody's floor.

The dinner conversation

Isn't it interesting listening to these ancient Romans hanker after "the good old days"?

The paragraph at the bottom of page 1099, which describes a candidate for office outdoing his rival in putting on the grandest gladiatorial show, is a glimpse of Roman politics. Like everything in the story, this part is probably exaggerated--but not out of recognition. The grandstanding political campaign was born and perfected in ancient Rome.

Anti-intellectualism, as we see on page 1100, was at least as prevalent then as it is now. Echion the rag merchant, after describing Agamemnon as "off your head with all that reading," promises to send his son to be tutored by him "if God spares him." This last remark, like the skeleton, is a rather jarring reminder of the high death rate in the ancient world. Children were especially at risk; Roman parents were in the habit of decking their offspring with bracelets or necklaces embedded with bits of amber to ward of the ever-present evil eye.

I wonder if we're supposed to believe the freedman friend who says his father was a king (1102). This is, of course, possible--the Romans felt everyone outside the Empire was a barbarian, and taxed non-citizens, and he claims he sold himself into slavery in hopes of becoming a citizen one day. Still, I can't help feeling it isn't incredibly probable. Well, if he isn't telling the truth, who's going to check up on his story?

On page 1103, this same freedman describes his life as a slave: "I had people in the house who tried to trip me up one way or another, but still--thanks be to his guardian spirit!--I kept my head above water." Why his guardian spirit, rather than my guardian spirit? Because the former slave is talking about one of his master's Lares, the guardians of the people within a household. The master was the head of the household, and everything inside it, including the spirits, belonged to him.

The same speaker mentions Saturnalia, which was an annual holiday at the winter solstice that combined elements of today's Christmas and New Year celebrations (Saturn, associated with Cronus, has morphed into our "Old Father Time"--now you know what he's doing with that sickle!). Gifts of candles and toys for children were given, and homes were decked with greenery. These elements were incorporated into Christmas celebrations when the Emperor Constantine first made Christianity the official religion of Rome in the 4th century A.D. It was at that time that the celebration of Christ's birth was fixed at December 25, which according to Constantine's calendar was the date of the solstice. For more details click here or run a web search on the keyword "Saturnalia."

Fortunata

Fortunata's character is a sign of just how much a woman's role in ancient Rome differed from that of ancient Greece. When Trimalchio's friend Habinnas shows up, he asks almost immediately why Fortunata isn't at the table. Respectable Greek women never ate at the table along with the men.

Fortunata, too, is breaking the sumptuary laws, as Roman women were strictly limited in how much jewelry, by weight, they were permitted to wear. Six and a half pounds was not within the weight limit.

Notice, too, that she has served as a partner to Trimalchio in his business: when he needed money after he lost his entire fleet of wine-bearing ships, "she sold off all her gold trinkets, all her clothes, and put ten thousand in gold pieces in [Trimalchio's] hand" (1109).

We've come a long way from Andromache, who was only able to help her husband by climbing up onto the walls of Troy and looking out for weak spots.

About the author

For more information about Petronius and the entire Satyricon on line, click here. There's an excellent introduction about Petronius himself. But beware--the person who coded it did it all as one page, so even though it's only text it takes forever to load completely. And whatever you do, don't print it unless you've specified to your computer to only print a certain number of pages. Don't forget: the Satyricon, fragmentary though it is, is an ancient novel. So that web "page" is the length of a short book.