AFRODITH

(Aphrodite)

Goddess of Love and Other Beautiful Things

Roman Name: Venus

Roman Name: VenusSacred Regions: Cyprus, Cythera Sacred Plant: Myrtle Totem Animals: Dove, swans, sparrows How to Identify Her: Often carrying a mirror. Sometimes Aphrodite has a knot of hair shaped kind of like a dog bone on top

of her head

|

Images of Aphrodite, courtesy of The Library of Frederick John Kluth

The painting at the top of this page is Sandro Botticelli's "Venus and Mars." Like any self-respecting goddess of love, Aphrodite has a sweetheart: Ares, the god of war (Roman name Mars). This gives a whole new meaning to Paul McCartney's old song, "Venus and Mars are All Right Tonight."

Unfortunately for all the Olympians' peace of mind, Aphrodite also has a husband: the misshapen smith god, Hephaestus (or Hephaistos, or Vulcan). Her scandalous philandering is said to cause her husband no end of grief, and once induced him to go so far as to craft an unbreakable net to throw over the lovers while they slept and call all the rest of the gods to come and make fun of them. If this was a plan to shame Aphrodite out of her affair, it backfired; it just made her mad and more determined to carry on with Ares than ever. In the painting, by the way, you'll notice that Aphrodite's little helpers in the form of satyrs are carrying off Ares' armor. This theme of "war disarmed by love" is a common one in western art, though the actual disarming is usually carried out by Aphrodite's favorite son Eros--especially in the later, Roman tradition, where the dignified adult Eros became the mischievous boy Cupid. Ironically, it was probably Aphrodite's husband who made the armor.

The other image is the famous Venus de Milo, so called because this Hellenistic statue, dating back to around the second century B.C., was originally discovered on the Cycladic island of Melos. Generally, Aphrodite is the only goddess whom you will see depicted in the nude. This tradition seems to have started with the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles, whose undraped Aphrodite of Knidos (or Cnidus) caused several scandals (not the least of which is the origin of the "flaw" mentioned by Pliny!), but was of such startling beauty it withstood them all.

The story has it that the union between Aphrodite and Hephaestus was a marriage of convenience engineered by Aphrodite's father, Zeus, in order to convince Hephaestus to stay on at Olympus and create beautiful metal objects for the gods even after Hephaestus's mother Hera, horrified at her baby's appearance, had cast him out of heaven and down to the ground--an act that resulted in a permanent limp (this is one story; another says that he fell to the ground when he tried to rescue his mother from being abused by Zeus). More on that when it's Hephaestus's turn to be Deity of the Week.

I know what you're thinking but it's not true, even though when Amanda remarked that life on Olympus generally sounds like the Jerry Springer show she did have a point. This particular relationship, however, was not an incestuous marriage. Although Zeus and Hera are man and wife, Aphrodite is Zeus's daughter by Dione and Hera supposedly gave birth to Hephaestus all by herself, without male intervention. No, I don't know the details on how she managed to pull it off. Some versions have it that she did so because she was jealous of the fact that Zeus gave birth to Athena "unaided"--poor Metis once again doesn't get any credit!

Then again, there's some confusion about Aphrodite's birth, as well. Although Homer claims Aphrodite's mother is Dione, another theory, described by Hesiod in the Theogony, is a little more bizarre (Read the gruesome details here). As Powell mentions, the newborn Aphrodite floated near Cythera and washed up at Cyprus, which is why she is often called either Cytherea or the Cyprian. The word aphros means "foam," but as Powell tells us, Hesiod's derivation of "Aphrodite" from "aphros" is inaccurate, a false etymology. Some scholars, incidentally, claim that the origin of sea foam is a sexual one, resulting from semen in Cronus's genitalia when they fell into the water. While that would certainly explain how the foam produced Aphrodite--similar to the way Hephaestus's semen produced Erichthonius on Athena's thigh (if you haven't read about this yet, you'll find it in this week's reading assignment in Chapter 12)--I can't help but feel that the idea is a bit unsettling, to say the least.

On pages 112-113, Powell mentions Plato's Symposium, a long dialogue about the nature of love. Powell concentrates on a story told by Aristophanes (the comic playwright who wrote The Clouds, which I mentioned in last week's page about Zeus), but another speaker at the symposium gives an interesting account that explains these two differing accounts of the goddess's birth: the Aphrodite born of sexual union, Aphrodite Pandemos, rules over the sexual impulse and erotic love, while the parentless Aphrodite from the sky, Aphrodite Urania, is the higher impulse of the affections. The Roman philosopher Lucretius rolled both of these functions into one in the invocation that begins his masterwork, De Rerum Natura ("On the Nature of Things"), in which he praises Venus as the source of all life.

Aphrodite had a number of affairs with mortals, many of which ended unhappily. In the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, excerpted on pages 156-162 of your textbook, the mortal King Anchises is well aware of this and she has to lie about her goddess status in order to seduce him. When he figures out what's happened the morning after he is horrified, remarking that "the mortal who mates with a goddess undying can never again be a man" (lines 174-175). Luckily for him his fears for his own safety turn out to be groundless, and the famous Trojan hero Aeneas is born of the encounter.

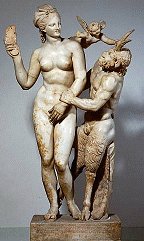

Contrary to popular belief,

Aphrodite isn't always in the mood. My favorite image of her is the

one to the right, a statue from the Hellenistic period (about 4th century B.C.)

that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. As a laughing Eros

peeks over her shoulder, she raises her sandal to playfully slap away the goat-footed

god Pan, who is trying to seduce her. The statue is sometimes referred to as "the

slipper slapper." Pan doesn't seem too put out; at any rate, he's smiling.

Contrary to popular belief,

Aphrodite isn't always in the mood. My favorite image of her is the

one to the right, a statue from the Hellenistic period (about 4th century B.C.)

that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. As a laughing Eros

peeks over her shoulder, she raises her sandal to playfully slap away the goat-footed

god Pan, who is trying to seduce her. The statue is sometimes referred to as "the

slipper slapper." Pan doesn't seem too put out; at any rate, he's smiling.

As stated above, Aphrodite's favorite animals were all graceful birds. The doves and swans might make the most sense to us today, but anyone who has seen the famous Spring Fresco from Akrotiri on the island of Thera (Santorini) has noticed the mating swallows that decorate it, so art historians theorize that they must have been associated with sexuality somehow in the Bronze Age. Aphrodite is sometimes described as riding in a chariot pulled by doves. One can't help thinking that must take an awful lot of doves, but then, she is a goddess. Maybe she's divinely light and airy.

Aphrodite's plant was the myrtle, which was used in wedding wreaths

all the way up through the medieval period and is mentioned as an image

associated with marriage in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's honeymoon poem,

"The

AEolian Harp." An old story explaining the

large pores on the underside of myrtle leaves claims that when Aphrodite

caused Theseus's young bride, Phaedra, to fall in love with her hapless

stepson Hippolytus

(who had been paying too much attention to Artemis in his religious

observations), Phaedra developed the habit of lurking behind a myrtle bush in

order to watch Hippolytus exercise in the nude. In her frustration, she took

to jabbing at the leaves with the sharp spike that fastened her brooch.

The goddess of love can prove to be a powerful ally, as Pygmalion (pages 154-156 in your text) and Hippomenes found out. She also has a strong sense of family loyalty. For instance, one of the reasons she fought on the Trojan side during that famous war--and was even wounded on the battlefield--was a desire to protect her son Aeneas. That's right, the same Aeneas born from her encounter with Anchises. Also during the Trojan War she lent her magic girdle (not what you're thinking; it means a broad belt) of seduction to her stepmother Hera for the purpose of distracting and seducing Zeus in the Iliad Book 14.

You may have heard that Aphrodite was a difficult mother-in-law, at least according to the story of Psyche, but that's a later interpolation and is not a part of the Greek tradition. The first known example of the Psyche story is in Lucius Apuleius's Metamorphoses, written in the second century A.D., an expanded adaptation of Lucian's satirical tale of The Golden Ass.

To read more about Aphrodite, click here and here for entries from the Encyclopedia Mythica and Perseus, click here for an overview of myths about Aphrodite in capsule form, and here for ancient texts referring to her.