AFRODITH

(Aphrodite)

Goddess of Sexual Passion

Roman Name: Venus

Roman Name: VenusSpouse: Hephaestus (Hephaistos, Roman Vulcan) Sacred Regions: Cyprus, Cythera Sacred Plant: Myrtle or rose Totem Animals: Dove, swans, sparrows How to Identify Her: Often carrying a mirror. Sometimes Aphrodite has a knot of hair shaped kind of like a dog bone on top of her head, or her hair flowing loose. Statues from or after the 4th century B.C.E. (but not before) often depict her totally or partially nude.

|

The painting at the top of this page is Sandro Botticelli's "Venus and Mars." As we have already discussed in class, like any self-respecting goddess of love, Aphrodite has a sweetheart: Ares, the god of war (Roman name Mars). I've always felt that his gives a whole new meaning to Paul and Linda McCartney's old song, "Venus and Mars are All Right Tonight."

Unfortunately for all the Olympians' peace of mind, Aphrodite also has Hephaestus. Her scandalous philandering causes him no end of grief, and in this week's assigned reading our textbook gives us Homer's story of the time he went so far as to craft an unbreakable net to throw over the lovers while they slept and call all the rest of the gods to come and make fun of them. If this was a plan to shame Aphrodite out of her affair, it backfired; it just made her mad and more determined to carry on with Ares than ever. Not to mention the fact that after this revelation the gods made fun of Hephaestus--and expressed begrudging admiration for Ares!

In the painting, by the way, you'll notice that Aphrodite's little helpers in the form of satyrs are carrying off Ares' armor. This theme of "war disarmed by love" is a common one in western art, though the actual disarming is usually carried out by Aphrodite's favorite son Eros--especially in the later, Roman tradition, where the dignified adult Eros became the mischievous boy Cupid. Ironically, it was probably Aphrodite's husband, in his role as smith to the gods, who made the armor.

In the version painted in 1824 by the French artist Jacques-Louis David (click here if you want to see it, and click again on the painting for a high-resolution version; the link will open in a separate window so you won't lose contact with this deity page), Cupid is aided in this disarming action by the three graces while his mother replaces Mars's helmet with a wreath of flowers. I think the two smooching doves that hide the war god's private parts are a particularly inspired touch.

The other image at the top of the page is the famous Venus de Milo, so called because this Hellenistic statue, dating back to around the second century B.C., was originally discovered on the Cycladic island of Melos (the Cyclades are a series of Greek islands that are roughly arranged in a circle, a kyklos, around Apollo's sacred island of Delos). Generally, Aphrodite is the only goddess whom you will see depicted in the nude. This tradition seems to have started with the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles, whose undraped Aphrodite of Cnidus (or Knidos) caused several scandals (not the least of which is the origin of the "stain" mentioned by Pliny in that quotation--eeeeew!), but was of such startling beauty it withstood them all.

As we discussed in Week Two, the story has it that the union between Aphrodite and Hephaestus was a marriage of convenience engineered by Aphrodite's father, Zeus, as a bribe to convince Hephaestus to stay on at Olympus and create beautiful and useful metal objects for the gods. Hephaestus needed to be persuaded because he was understandably angry after his mother Hera, horrified at her baby's appearance, had cast him out of heaven and down to the ground--an act that resulted in a permanent limp. This is the most common variant. Homer claims in Book 1 (but not Book 18!) of the Iliad that Hephaestus fell to the ground and was injured when he tried to rescue his mother from being abused by Zeus. Either way, you can see why he was reluctant to stick around.

Although Homer claims Aphrodite's mother is Dione, the alternative theory described by Hesiod in the Theogony has its adherents. The newborn Aphrodite, sprung from the sea, floated near Cythera and washed up at Cyprus, which is why she is often called either Cytherea (Kythereia), pronounced "kee-ther-EE-uh," or simply the Cyprian, pronounced "SIP-ree-un." (Interesting factoid: in 19th-century England, the word "Cyprian" was slang for "prostitute." Most wealthy young men in those days had a solid background in classical literature, and they applied it in some interesting ways). The modern residents of Cyprus--who are called Cypriots, not Cyprians!--have gone so far as to reinstate a festival in her name, though to be honest any connection with the ancient goddess is tenuous at best.

The word aphros means "foam," but many classical scholars think that Hesiod's derivation of "Aphrodite" from "aphros" is inaccurate, a false etymology. Some commentators claim that the origin of sea foam is a sexual one, resulting from semen left in Cronus's genitalia when they fell into the water. While that would certainly explain how the foam produced Aphrodite--similar to the way Hephaestus's semen produced Erechtheus by ejaculating onto Athene's thigh--I can't help feeling it's a little...well...unsettling, to say the least. Just when you thought it was safe to go swimming at the beach...

Pages 76-77 of Classical Mythology summarize Aristophanes' delightful speech from Plato's Symposium, a long dialogue about the nature of love (you are not expected to read the Symposium; I just wanted to provide a link to the entire thing in case you're interested). Another speaker at the symposium gives an interesting account that explains how these two variant versions of the goddess's birth came to be: the Aphrodite born of the sexual union of Zeus and Dione, Aphrodite Pandemos, rules over the sexual impulse and erotic love, while the parentless Aphrodite from the sky, Aphrodite Urania, is the higher impulse of the affections.

The Roman philosopher Lucretius rolled both of these functions into one in the invocation that begins his masterwork, De Rerum Natura ("On the Nature of Things"--another long one; you needn't read past the first short line, where Lucretius switches gears) , in which he praises Venus as the source of all life and the "mother of Rome." For Lucretius, Venus seems to take on the function of the primordial Eros that Hesiod described in the Theogony.

Aphrodite had a number of affairs with mortals, usually of her own free will (the Anchises episode was an exception). The best known is her ill-fated relationship with Adonis. Adonis had a weird birth, even for a mythological character, and it was all Aphrodite's fault. His mother, the eastern princess Myrrha, fell in love with her own father (for details, see the reading assigned for Wednesday). Ovid describes her metamorphosis into a myrrh tree. At the time Myrrha was pregnant with the fruit of her forbidden love, so after she came to term the bark split open and Adonis popped out. He must have smelled wonderful as well as being uncommonly beautiful; myrrh was one of the most valued perfumes of the ancient world. It also had a number of valuable medicinal uses, which is why the New Testament describes it as an appropriate gift for the Christ child.

Perhaps the reason Adonis is so famous is that not only was he the center of an important cult, but he has been an extremely popular subject for poets ever since. Most famous, perhaps, is William Shakespeare's magnificent lyric poem, Venus and Adonis (and here you thought Shakespeare only wrote plays!). It's a very long poem so you needn't read it all just now, if you're pressed for time... but if you're an English major, at some point in your career you probably should do so.

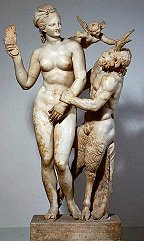

Contrary to popular belief,

Aphrodite isn't always in the mood for love. My favorite image of her is the

one to the right, a statue from somewhere around the 4th century B.C.E.,

that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. As a laughing Eros

peeks over her shoulder, she raises her sandal to playfully slap away the goat-footed

god Pan, who is trying to seduce her. The statue is sometimes referred to as "the

slipper slapper." Pan doesn't seem too put out; at any rate, he's smiling. So,

for that matter, is Aphrodite.

Contrary to popular belief,

Aphrodite isn't always in the mood for love. My favorite image of her is the

one to the right, a statue from somewhere around the 4th century B.C.E.,

that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. As a laughing Eros

peeks over her shoulder, she raises her sandal to playfully slap away the goat-footed

god Pan, who is trying to seduce her. The statue is sometimes referred to as "the

slipper slapper." Pan doesn't seem too put out; at any rate, he's smiling. So,

for that matter, is Aphrodite.

As evidenced by the list of attributes in the table at the top of this web page, Aphrodite's favorite animals were all graceful birds. The doves and swans might make the most sense to us today, but anyone who has seen the famous Spring Fresco from Akrotiri on the island of Thera (Santorini) has noticed the mating swallows that decorate it (whether male and female pairs or macho males sparring in the mating season, as cynically suggested in the text below the picture on the page linked to above), so art historians theorize that they must have been associated with sexuality in the Bronze Age. Aphrodite is sometimes described as riding in a chariot pulled by doves. One can't help thinking that must take an awful lot of doves, but then, she is a goddess. Maybe she's divinely light and airy.

Aphrodite's plant was the myrtle, which was used in wedding wreaths even during the Christian medieval period. Myrtle is mentioned as an image associated with marriage in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's honeymoon poem, "The AEolian Harp" (1795). This romantic poem about the poetic imagination contains what I consider to be one of Coleridge's least successful attempts to invoke atmosphere through the senses ("How exquisite the scents / Snatched from yon bean-field!") but hey, he was young and in love, so give him a break.

The association with roses is more commonly linked with Venus, Aphrodite's Roman counterpart. According to one legend, Venus's passion for the hunting-mad young man Adonis led her to disguise herself as Diana, the goddess of the hunt, in order to meet with him. Unused to the rough forest floor, she made the mistake of going without any shoes and tore her foot on the thorns of a wild rose bush. This explains why roses, hitherto all white, became pink and red; they were stained with her ichor (which is the word Homer uses for the liquid that flows in the veins of the gods; they do not have blood, as we thnetoi do).

Another old story explaining the

large pores on the underside of myrtle leaves tells us how Aphrodite

caused Theseus's young bride, Phaedra, to fall in love with her hapless

stepson Hippolytus. The young man had been paying too much attention to the virginal goddess Artemis

in his religious observations, at Aphrodite's expense, and dissing the idea of sexual love. You may recall

him as the speaker in Euripides' play who said he wished he could just leave a sum of money at a temple

and pick up a son of corresponding value in return. Phaedra developed the habit of lurking behind a myrtle

bush in order to watch Hippolytus exercise in the nude (standard practice in ancient Greece; in fact, our

word gymnasium comes from the Greek word gymnos, which means "naked"). In her frustration,

poor Phaedra took to jabbing at the leaves with the sharp spike that fastened the brooch that held her dress up.

An intriguing etiological myth, to say the least.

The goddess of love can prove to be a powerful ally, as Pygmalion and Hippomenes will find out in Wednesday's reading assignment. She also has a strong sense of family loyalty, despite Vandiver's emphasis on her association with sexual passion as opposed to companionship or fidelity. For instance, one of the reasons she fought on the Trojan side during that famous war--and was even wounded on the battlefield, as shown in this painting by the 19th-century Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique--was a desire to protect her son Aeneas. That's right, the same Aeneas born from her encounter with Anchises. Here's the passage that recounts the incident (note how Homer's remark, "weak as men are now," seems to support his contemporary Hesiod's description of a separate "race of heroes" different from modern men). The ichor flowed that day!

Also during the Trojan War Aphrodite lent her magic girdle (not what you're thinking; it means a broad belt) of seduction to her stepmother Hera for the purpose of distracting and seducing Zeus in the Iliad Book 14. That was quite generous of her, considering the fact that the two goddesses took opposite sides in the conflict: Hera favored the Greeks, while Aphrodite was rooting for the Trojans because of her son--and also because the Trojan prince Paris had awarded her the famous golden apple designated "For the most beautiful." This event is known as the Judgment of Paris, although in light of the horrible consequences of that decision, perhaps it ought to be known as the bad judgment of Paris.

Return to the top of this page