|

|

Roman Name: Minerva Sacred City: Athens Totem Animal: The Owl Her Plant: The Olive Tree How to Identify Her: She's the lady in the helmet

|

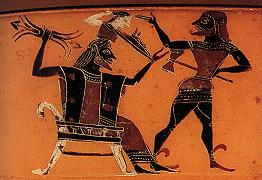

Every biography of Athene begins with her emergence fully grown from the head of Zeus, completely

clad in armor and hollering a loud war cry. Imagine the headache that must have given him.

Some accounts even claim that the headache was so bad he got Hephaestus to split his head

open with an axe so Athene could get out. See the picture at right, a vase painting signed by

an artist called Phrynos that dates back to the early classical period, for an illustration

of the Hephaestus with an axe version.

Every biography of Athene begins with her emergence fully grown from the head of Zeus, completely

clad in armor and hollering a loud war cry. Imagine the headache that must have given him.

Some accounts even claim that the headache was so bad he got Hephaestus to split his head

open with an axe so Athene could get out. See the picture at right, a vase painting signed by

an artist called Phrynos that dates back to the early classical period, for an illustration

of the Hephaestus with an axe version.

As I've mentioned a couple of times in class, the "splitting headache" story is one of the major examples of the chronological inconsistency of myth. If Hera gave birth to Hephaestus out of revenge for Zeus's parthenogenic production of Athene--which would assume his appearance occurred after the fact--then how is it he was around to free her with the axe? Don't try to think about this one too hard or you, too, will suffer from a splitting headache. At any rate Hephaestus is nowhere in sight on the vase painting that is shown on the cover of our text; instead we have two unidentifiable goddesses, Poseidon, and Ares (but isn't he usually Hephaestus's kid brother, produced when Hephaestus came out unattractive?), with the little winged figure of Nike--a victory goddess, often associated with images of Athene and often shown small like this--crouching beneath Zeus's throne.

Whatever the case, every summer the ancient Athenians celebrated this miraculous birth at a gigantic birthday party known as the Panathenaia (see Chapter One Classical Mythology for further details; Harris and Platzner use the Latinized spelling Panathenaea).

The version that claims that Athene's mother was Metis, the goddess whom Zeus swallowed whole before she gave birth--so make that a stomach ache as well as a headache--has to do with yet another one of those dire prophecies. As Vandiver mentioned in her Trojan War lecture, it's very similar to the Thetis story. Zeus had reason to fear that if Metis had a son he would be too powerful and perhaps there would be another palace coup at Olympus. After all, Zeus's father and grandfather before him had both lost their places due to filial usurpation. Unfortunately Metis was already pregnant, so Zeus followed his own father's example but did him one better by swallowing mother along with unborn child.

Luckily for Zeus, Athene turned out to be a girl, though she is very much a tomboy. She's Zeus's favorite child; he'll usually support her in any enterprise she takes on and vice versa. Unlike the rest of his squabbling progency, Zeus knows he can always count on Athene. In some stories, he even lets her borrow his thunderbolts.

The Greek word for virgin is parthenos, a word that was frequently attached to Athene's name as an epithet. So it should be obvious that the Parthenon, the most striking and famous building on the Athenian Acropolis, was built in honor of Athens' patron. This Greek root has found its way into our own language in the term "parthenogenesis," which means "virgin birth" and is applied by biologists to the process where living things produce asexually... including Zeus. The word is also used to describe the birth of Christ and the birth of the Buddha, both sons of mothers who were impregnated by means of divine intervention.

The fact that she's a virgin goddess doesn't mean Athene doesn't like men. She is very interested in masculine pursuits, especially war strategy. Unlike Ares' berserker philosophy, a great part of Athene's wisdom is in knowing when not to attack. Remember how in Book I of the Iliad, when Achilles draws his sword and threatens to slaughter Agamemnon, Athene comes up behind him and grabs him by the hair? She then privately suggests to him, unheard and unseen by any of the other men present, that this particular move would not be very wise strategy. Unlike Apollo who shoots from afar, Athene usually prefers a more "hands-on" approach.

|

So intimate was Athene's relationship with her favorite people, she even appeared on grave markers, such as the one pictured here. Her pose, leaning on her spear for support in her grief, is a touching depiction of profound and genuine mourning for the deceased.

Always ready to reward quick thinking, Athene also took a deep personal interest in the affairs of "wily Odysseus" and in Achilles, who (unlike poor Ajax the greater) was as clever as he was strong and handsome. She sided with the Greeks rather than the Trojans during the Trojan War, not only because of her fondness for her proteges Achilles and Odysseus but also because of that unpleasant affair where Paris declared Aphrodite more beautiful than Athene and Hera.

Another protege was Perseus, the slayer of the snake-haired gorgon Medusa. As described in the caption to the gruesome illustration in our textbook, he was so grateful he bestowed the gorgon's head, snakes and all, upon Athene in return for her assistance. This is why Athene is usually depicted wearing a snake-trimmed shield or cloak called the aegis, which produced instant widespread panic whenever she shook it. The aegis also had a protective function for those she sheltered beneath it; thus the phrase "under the aegis of" someone or something who protects or sponsors you.

The cloak itself is usually described as a gift from her father--you may recall from our first week's Featured Deity (of course you do!) that the aegis was made from the skin of the goat

Amalthea who had suckled Zeus when he was a baby--but, as usual, there's an alternative account. In this

story, which admittedly was not nearly as popular as the Zeus alternative, it's a gift from her

father in a more gruesome sense. If it is Amalthea's skin (or indeed Pallas's skin), the snakes

seem to have been Athene's own addition as a fashion accessory. If you'll

look closely, usually you'll see that she is wearing Medusa's severed head as a kind of brooch.

Since so many ancient statues have lost their heads, you can't always identify the subject by looking at

the hairstyle or face. But the statue at right is clearly Athene: even though her helmet is gone, the aegis

speaks to us loud and clear.

The cloak itself is usually described as a gift from her father--you may recall from our first week's Featured Deity (of course you do!) that the aegis was made from the skin of the goat

Amalthea who had suckled Zeus when he was a baby--but, as usual, there's an alternative account. In this

story, which admittedly was not nearly as popular as the Zeus alternative, it's a gift from her

father in a more gruesome sense. If it is Amalthea's skin (or indeed Pallas's skin), the snakes

seem to have been Athene's own addition as a fashion accessory. If you'll

look closely, usually you'll see that she is wearing Medusa's severed head as a kind of brooch.

Since so many ancient statues have lost their heads, you can't always identify the subject by looking at

the hairstyle or face. But the statue at right is clearly Athene: even though her helmet is gone, the aegis

speaks to us loud and clear.

The epithet "Pallas," by the way, may or may not refer to the giant of that name. It might also derive from the verb pallo, to brandish a spear (Athene usually carries one), or from a word meaning a robust young person, a maiden.

In the statue to the left, a modern German copy of the

famous 40-foot Athene that once stood beside the Parthenon, Athene's helmet and aegis

are covered with gold leaf. No, that is not a golden apple in her hand! She lost the apple to

Aphrodite, remember? If you'll look more closely you'll see that it's a gold ball that serves

as a base for a smaller image of the winged goddess Nike. As I mentioned above, Nike and

Athene are very closely related and are often shown together, and there is a small temple to

Nike at the gate of the Acropolis. The relationship arises naturally from Athene's function

as war strategist.

In the statue to the left, a modern German copy of the

famous 40-foot Athene that once stood beside the Parthenon, Athene's helmet and aegis

are covered with gold leaf. No, that is not a golden apple in her hand! She lost the apple to

Aphrodite, remember? If you'll look more closely you'll see that it's a gold ball that serves

as a base for a smaller image of the winged goddess Nike. As I mentioned above, Nike and

Athene are very closely related and are often shown together, and there is a small temple to

Nike at the gate of the Acropolis. The relationship arises naturally from Athene's function

as war strategist.

Inside the temple itself there was a second statue, designed by the Parthenon's architect, Pheidias. This second statue was a gold-and-ivory masterpiece (the technical adjective to describe a gold and ivory statue is "chryselephantine," since the word chrysion is Greek for "gold" and, well, the "elephant" part should be obvious). Pheidias's chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Like the Zeus statue, the Athene statue has been lost to time, but we still know basically what it looks like from images on coins. We also know, from evidence supplied by the second-century satirist Lucian, that these statues were hollow and supported by a core with bars and props inside to hold them up--a favorite home for mice, who could sometimes be heard scampering around inside.

A full-sized reproduction of the Pheidias statue has been constructed out of a fiberglas alloy and set up inside the reconstruction of the Parthenon in Nashville's Centennial Park. Scroll down to get a look at the statue. Don't miss the sacred serpent at her side, inside of her shield. This photo was taken before they gilded her in 2002--which looks closer to the ancient original but to modern eyes appears rather gaudy. You can see the gilded version here if you want to, but I don't think you'll like it much. Well, I know I don't.

If you're wondering whether that red lipstick effect is authentic, I shudder to admit that the answer is yes. The features of statues were brightly painted in the ancient world, even when they adorned the outside of buildings.

Despite her willingness to champion individuals who pleased her, Athene could be a harsh mistress. For one thing, she seems to get a kick out of fooling her followers by taking on various disguises. Her various disguises in the Odyssey, which she usually assumes to see if Odysseus can recognize her, almost take on a flirtatious nature as they banter back and forth and she teases him until he figures out it's her. She loves cleverness, so she tends to be rather tricky herself.

But her attentions could be less benign: she visited some pretty strong punishments upon mortals who offended her. According to one variant story, the Theban seer Tiresias was struck blind for accidentally catching sight of Athene while she was bathing in a river. Too bad for him it wasn't Aphrodite instead; she probably would have invited him to join her. Then again, things could have been worse. Remember what happened to Actaeon when he stumbled across the bathing Artemis.

Arachne, who is mentioned briefly in our textbook, was

turned into a spider for daring to challenge Athene to a weaving contest--or, as Ovid says, for

weaving illustrations of stories

insulting to the gods into her contest entry. The picture

here is taken from a children's storybook and shows Arachne, already a spider, perched

above her offensive images, in this case a picture of Athene playing the flute and a picture

of Zeus once again pursuing some mortal beauty. But Arachne has had her compensation now that

the internet has come onto the scene. After all these years of abuse by people who don't like spiders,

she's become the unofficial patron goddess of web page designers.

Arachne, who is mentioned briefly in our textbook, was

turned into a spider for daring to challenge Athene to a weaving contest--or, as Ovid says, for

weaving illustrations of stories

insulting to the gods into her contest entry. The picture

here is taken from a children's storybook and shows Arachne, already a spider, perched

above her offensive images, in this case a picture of Athene playing the flute and a picture

of Zeus once again pursuing some mortal beauty. But Arachne has had her compensation now that

the internet has come onto the scene. After all these years of abuse by people who don't like spiders,

she's become the unofficial patron goddess of web page designers.

Why was it offensive to show Athene playing the flute? According to myth, Athene invented the flute and was quite delighted with it until she caught sight of herself in a pond and saw how ridiculous she looked with her cheeks all puffed out. Apparently being a virgin doesn't mean she's altogether free of vanity. She threw the flute to the ground in disgust and abandoned it where, some say, it was later found by Pan. Since he's half a goat anyway he isn't nearly as concerned with appearances, and he was happy to take on the flute as one of his own attributes. Other accounts claim that Pan himself invented the flute (the story of Syrinx), but this isn't a page about Pan so you'll have to look that one up for yourself. And, of course, the Homeric Hymn to Hermes claims the flute's invention for Pan's father, Hermes.

As Athene Polias, another of her

epithets, Athene was the guardian of the city. This does mean cities and civilization in

general, but her favorite city is, naturally, Athens. To the left is an ancient Athenian coin, bearing

Athene's sacred owl and olive branch. There even used to be a catch saying, kind of like the

British adage about "bringing coals to Newcastle" (Newcastle is located in a rich coal-producing

area, so the phrase means that you are trying to do something absolutely unnecessary), about

"bearing owls to Athens."

As Athene Polias, another of her

epithets, Athene was the guardian of the city. This does mean cities and civilization in

general, but her favorite city is, naturally, Athens. To the left is an ancient Athenian coin, bearing

Athene's sacred owl and olive branch. There even used to be a catch saying, kind of like the

British adage about "bringing coals to Newcastle" (Newcastle is located in a rich coal-producing

area, so the phrase means that you are trying to do something absolutely unnecessary), about

"bearing owls to Athens."

For more pictures of ancient Greek coins, see this gorgeous collection for sale on line... Just don't get carried away and buy any!

Before Athene could become Athens' patron, you'll recall that she had to win the city away from Poseidon, who was also interested in the place. Now, you may have been asking yourself why the gods were so excited about this rather rocky, dry little polis with such lousy soil it didn't produce much except really good clay for pottery, but the answer is simple: most of these mythological accounts were passed down from Athenian sources. And because the pottery industry was so well developed there, most of the best vase paintings--the source of a lot of our information about everyday life and beliefs--come from Athens, too.

Since two powerful gods contested the right to preside over the city, it was decided that whoever produced the best gift for the citizens would win out. Athene struck the ground with her spear and up sprang an olive tree. Poseidon did the same thing with his trident and one of two things emerged from the ground: either the first horse, or a stream of water. The water version says that while the spring looked good, it turned out to be salty--after all, Poseidon is the god of the sea--and therefore undrinkable. The horse version makes more sense to me, because I just can't imagine a deity so dumb that he would consider a stream of saltwater to be a useful gift (allegorical commentators later claimed that it was a symbol for the unsurpassed naval power that would bring Athens to imperial glory in the fifth century B.C.E.... but that seems a bit too "after the fact" in my opinion, since most of these myths are a lot older than the classical period). Horses are sacred to Poseidon, perhaps because of the very old notion that the sea foam on the crests of waves resembles galloping white horses, perhaps because he had former associations as a fertility god, so the horse story is logical and makes sense.

If you think horses are more useful than olives, you

couldn't be more wrong. Horses were rare and very valuable, and thus only available to

the upper classes. People like you and me would have been more likely to have used donkeys

for transport of ourselves and our stuff. Aristocrats of the second class were known as hippeis, which

literally meant "horsemen" or "knights," and one of the requirements of their social position

was that the family had to own at least one horse. Olives, on the other hand, are available

to all. Also, although it was Poseidon who invented the horse, it was clever

Athene who invented the chariot and bridle that made horses useful to human beings.

If you think horses are more useful than olives, you

couldn't be more wrong. Horses were rare and very valuable, and thus only available to

the upper classes. People like you and me would have been more likely to have used donkeys

for transport of ourselves and our stuff. Aristocrats of the second class were known as hippeis, which

literally meant "horsemen" or "knights," and one of the requirements of their social position

was that the family had to own at least one horse. Olives, on the other hand, are available

to all. Also, although it was Poseidon who invented the horse, it was clever

Athene who invented the chariot and bridle that made horses useful to human beings.

It's helpful too to keep in mind the fact that to the ancient Greeks, olives were not just a tasty garnish on a pizza. Olive oil was an absolute necessity for cooking, food preservation (no refrigerators!), lamp oil (no electricity!), skin lubrication (Athens is a very dry place, and Oil of Olay had not yet been invented), and even washing. Because water was so scarce and nobody had ever heard of soap, ancient Greeks--and later Romans--cleaned their skin by rubbing it with olive oil, then scraping oil and dirt off together with a scythe-shaped metal object called a strigel.

One thing the olive tree did not produce was wood for fuel, unless the tree fell down

by itself. To chop down an olive tree, even as late as the sixth century

B.C., was punishable by death. This sense of the olive tree's sacred

nature hung on long after Athene was no longer worshipped: in 1825, during the Greek War of

Independence, the Egypto-Turkish troops invaded the Peloponnesus and began a slash-and-burn

campaign. Theodore Kolokotronis, the commander of the Greek land troops, was

unphased by the wholesale slaughter that took place, but as he reported in his autobiography

he condemned his opponents as outright barbarians when he found out that in addition to people and

houses they were destoying all the olive trees. What's more, the destruction of olive trees is still a hot-button issue issue in

the middle east (see also this article from The Economist, October 15 2009, for a more recent example). People from technologically

advanced societies sometimes have a little trouble understanding why this destruction of olives is so significant.

A final word, regarding Athene as the goddess of wisdom. It might surprise you to know that it wasn't until the late classical period that she became the goddess of wisdom in the abstract sense, since that's how we usually think of her today. The reason for that is the revolution in writing that occurred as a result of the invention of the alphabet, and the explosion of literature that followed and provided us with most of our ancient texts. By the fifth century B.C.E., as the hero's code of conduct was in the process of being supplanted by that of the educated sophist, Athene's role in everyday life became increasingly important. It also changed somewhat; according to what my Greek teacher told me years ago, "sophia"--the root of the word sophist and the word we usually translate as "wisdom"--once referred to being clever with one's hands rather than with one's words... thus Athene's association with weaving. When the word's meaning changed, so did her duties as a god. Perhaps the best fusion of her various roles was achieved in a speech by an "Eleatic Stranger" in Plato's Statesman:

All things which we make or acquire are either creative or preventive; of the preventive class are antidotes, divine and human, and also defences; and defences are either military weapons or protections; and protections are veils, and also shields against heat and cold, and shields against heat and cold are shelters and coverings; and coverings are blankets and garments; and garments are some of them in one piece, and others of them are made in several parts; and of these latter some are stitched, others are fastened and not stitched; and of the not stitched, some are made of the sinews of plants, and some of hair; and of these, again, some are cemented with water and earth, and others are fastened together by themselves. And these last defences and coverings which are fastened together by themselves are called clothes, and the art which superintends them we may call, from the nature of the operation, the art of clothing, just as before the art of the Statesman was derived from the State; and may we not say that the art of weaving, at least that largest portion of it which was concerned with the making of clothes, differs only in name from this art of clothing, in the same way that, in the previous case, the royal science differed from the political?

To read more about Athene, click here and here for entries from the Encyclopedia Mythica and Perseus, click here for Carlos Parada's overview of myths about Athene in capsule form, and here for ancient texts referring to her. For more information than you could possibly use about Athene, check out her shrine on line.