DIONUSOS

(Dionysus, or Dionysos)

God of Wine, Theater, and the "Life Force"

Roman Name: Bacchus

Roman Name: BacchusSpouse: Princess Ariadne of Crete Sacred Regions: Thebes, Naxos Sacred Plant: Grapevines, ivy, pines Totem Animals: Leopards, panthers, goats How to Identify Him: Vine leaves, thyrsis. Often he holds a kylix (shallow cup) of wine.

|

In ancient art, the youngest member of the Olympic pantheon is usually depicted as

a handsome man with an ivy crown, though because he was the patron of the theater he was

sometimes represented by a mask only: in the classical period, tragic actors always wore masks.

He often has wild lions, tigers, or panthers near him, and is frequently shown sitting on their backs.

This typical mosaic

comes from an atypical source: Roman Britain. Similar mosaics have been found on the sacred island of Delos,

where he rides a panther and carries a tambourine, and in the buried city of Pompeii, where he is shown as a winged

god riding on the back of a tiger. This affinity for wild cats indicates his wild and uncontrollable nature.

The most famous image of Dionysus is painted on the interior of the 6th-century drinking cup pictured to the right. It depicts him right after he vanquishes the pirates (see the "Hymn to Dionysus" on pages 277-281 of Harris and Platzner's Classical Mythology). The transformed pirates look quite cheerful, don't they? It's almost as if they liked being turned into dolphins.

Other depictions show him as a young man, almost feminine, with curly hair--especially in his Roman form as Bacchus--but he can also be shown as a mature man with a full beard. This is unusual in a classical god; usually by the time the classical period came along they were consistently shown with or without a beard. Luckily for those who want to identify him in a work of art, the animals, the ivy, or the grapevines will almost always be there to identify him. The picture inside the table above is adapted from Nicolas Bertin's painting of Bacchus and Ariadne, c.1710-15, in which the god hoists a remarkably modern wine glass. In ancient depictions, the cup will generally be a shallow kylix, of the sort depicted in this statue:

Ariadne is Dionysus's wife, a princess of Crete who captured his heart and who became immortal

through his love. This is, of course, the same Ariadne who had the affair with Theseus, the clever

daughter of King Minos who gave him the ball of thread and told him the secret of how to

kill the minotaur and escape her father's labyrinth. Theseus left her behind on the Cycladic island

of Naxos while they were sailing home to Athens. Some

stories say she fell asleep and missed the orders to embark; others claim her lover was forced to

abandon her by direct order of the lovestruck god. Years later, Theseus married Ariadne's sister

Phaedra, but by that time he was quite a bit older and that youthful glamor seems to have worn off;

at any rate, Phaedra fell for his son instead (I know, I know, the mythological sources say that was all

angry Aphrodite's fault, but personally I have my doubts). You will recall from last week that Phaedra was the poor

lady who used her dress pin to mangle the underside of all those myrtle leaves outside her stepson's

gymnasium.

Ariadne is Dionysus's wife, a princess of Crete who captured his heart and who became immortal

through his love. This is, of course, the same Ariadne who had the affair with Theseus, the clever

daughter of King Minos who gave him the ball of thread and told him the secret of how to

kill the minotaur and escape her father's labyrinth. Theseus left her behind on the Cycladic island

of Naxos while they were sailing home to Athens. Some

stories say she fell asleep and missed the orders to embark; others claim her lover was forced to

abandon her by direct order of the lovestruck god. Years later, Theseus married Ariadne's sister

Phaedra, but by that time he was quite a bit older and that youthful glamor seems to have worn off;

at any rate, Phaedra fell for his son instead (I know, I know, the mythological sources say that was all

angry Aphrodite's fault, but personally I have my doubts). You will recall from last week that Phaedra was the poor

lady who used her dress pin to mangle the underside of all those myrtle leaves outside her stepson's

gymnasium.

Whatever the case, Dionysus saw Ariadne on the Naxos beach and fell for her at once. He suggested on the spot that she forget all about her lost love and set up housekeeping with him instead, up on Olympus. Talk about a cloud with a silver lining! Get dumped by a hero, become the wife of a god. And the ultimate Party God, yet! Perhaps the most famous Bacchus and Ariadne depiction (scroll down the page for additional depictions of Dionysus, including ancient ones), painted in by the Renaissance artist Titian in the 1520s, depicts the very moment of their first meeting. You can see Ariadne's arm reaching out toward the sails of Theseus's retreating ship (that tiny white thing just off her left shoulder) even as she turns toward the god, descending from his chariot in this midst of his rowdy followers. You can find a humongous 2-megabyte high resolution image of the picture here.

If you clicked on one of the Titian links above, you might have noticed the stars circling around Ariadne's head.

Dionysus was so smitten, he created a constellation in her honor. Greek brides and grooms wear crowns at their weddings

(this is the case even today, in Greek Orthodox weddings, though sometimes the crowns are garlands

of flowers), and the Corona Borealis, supposedly, is Ariadne's bridal crown. Unlike Titian's version, the actual

constellation is in the shape of a semicircle rather than a full ring. Here's a photo (use the mouse rollover feature to see a connect-the-dots version and find out what else

is in the galactic neighborhood).

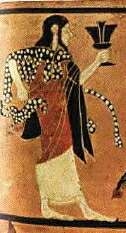

Wine was extremely important to the ancient

Greeks, and a libation was made to the gods before drinking, as well as on other

occasions. Antigone, the princess of Thebes who risked her life to bury her brother Polyneices and free

his spirit in the underworld, made a libation when she when she "sprinkled wine three times

for her brother's ghost" in line 293 of Sophocles' tragedy, Antigone (see page 709 of our textbook).

You could offer a libation by spilling a few drops on the ground or floor from your own cup, or you could use

a ritual vessel like the libation tripod pictured at right. Wealth was often measured in terms of how many

vineyards (sacred to Dionysus) or olive groves (sacred to Athene) a family owned.

Wine was extremely important to the ancient

Greeks, and a libation was made to the gods before drinking, as well as on other

occasions. Antigone, the princess of Thebes who risked her life to bury her brother Polyneices and free

his spirit in the underworld, made a libation when she when she "sprinkled wine three times

for her brother's ghost" in line 293 of Sophocles' tragedy, Antigone (see page 709 of our textbook).

You could offer a libation by spilling a few drops on the ground or floor from your own cup, or you could use

a ritual vessel like the libation tripod pictured at right. Wealth was often measured in terms of how many

vineyards (sacred to Dionysus) or olive groves (sacred to Athene) a family owned.

Libations were performed on sacred occasions, but also whenever people embarked on a new enterprise--like our modern custom of smashing a champagne bottle against the prow of a maiden ship--and even on an everyday basis, such as before meals. Good thing there was no wall-to-wall carpeting in the dining rooms back in those days.

Dionysus is usually connected to wine and mystic rituals, but he has many layers to him and

is one of the most mysterious of the Olympians, as well as having possibly the most marked

dual nature of all of them--which is pretty impressive, since almost all of the gods seem to exhibit

two very different sides.

According to the most common account, Dionysus's duality began in the womb, when he was born to Zeus and the mortal Princess Semele, daughter of the King of Thebes. As usual, once Hera found out she came up with a plan to keep the child from growing up. The classicist Barry B. Powell makes an intriguing suggestion that her persecution might not be due only to jealousy this time; as he puts it, "It is not surprising that Hera, protectress of the family, would oppose the raging god who excited married women to madness and caused them to forget their duty to husband, family, and community" (Powell, Classical Myth 275).

|

As the child god matured his friends were satyrs, nymphs, and other forest creatures, and he would never forget his childhood companions. These, too, are common elements in images of Dionysus, even after he's grown up.

But Hera hadn't forgotten him, and as a last resort she inflicted him with a madness similar to drunkenness that sent him roaming around Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, and even Israel, followed by his faithful retinue which refused to desert him in his time of need. According to some myths Nysa or Nyse was the name of the nymph who raised him as well as the place where he was raised, and she was said to be buried in Israel in "Nysa Schitopolis," now known as Bet Shean.

His travels suggest to some scholars that he is not an original god of Greece but was adapted from other neighboring countries, a foreign origin that would explain why he is a latecomer on the Olympian scene, taking Hestia's place on the divine council. Supposedly, quiet, hearth-dwelling Hestia gave up her position with relief because she was tired of dealing with her quarrelsome relatives, but the other goddesses were not so pleased because the substitution of a god for a goddess upset the gender equity among the Olympians. Instead of having six major gods and six major goddesses, Hestia's resignation and Dionysus's appearance on the scene led to an unequal seven/five division of power.

Another story concerning the birth of Dionysus is connected to Demeter. In this case it is said he was her child, but when he was born the Titans, acting upon Hera's orders, tore him apart. Zeus saved the heart and gave it to Semele to swallow; thus Dionysus was born again. The fact that according to both legends he is twice born is one of the main reasons for his connection to mystic rituals, and a parallel with some of the elements of the Orphic rituals and Christianity. Like the grapevine, which must be cut back every year if it is to flourish, Dionysus was cut down only to rise again. His connection to Demeter and this "twice-born" nature made him a part of agricultural rituals and celebrations even before he was known as "god of wine."

While he was in Asia he met the Great Goddess Cybele, the goddess who turned Atalanta and

Hippomenes into lions for having sex in her temple precincts. Cybele was another deity of eastern

origins who, while initiating Dionysus into her Mysteries, cured him of his madness and made him realize

his godliness.

|

The oracle in Delphi explained the problem to the Athenians, who then built a temple to Dionysus and celebrated him as they should. In fact, it was said by some that between January and July, Dionysus took Apollo's place at Delphi, which would solidly establish him as a major player in the god business.

Dionysus and Apollo are often contrasted with one another, as in Nietzsche's idea of the "Apollonian" and the "Dionysian" sides of our personalities, where Apollo represents the rational individual and Dionysus represents the irrational animal (or herd) instinct. Here is the idea again in Nietzsche's own words (admittedly, a lot harder to comprehend easily in this version! Click at your own risk!).

Because madness is an integral part of Dionysus story and drinking wine is connected

to losing control, Dionysian Festivals have to do with losing one's self during celebration.

According to the famous mythographer Walter Burkert, this has to happen in a crowd, as

a shared experience. It doesn't have to come through being drunk; the crowds and the ritual

itself cause one to lose one's individual self during the celebration.

The stories of horrific end that came to the Minyads, King Pentheus of Thebes (Dionysus' own cousin!), and others who denied Dionysus's divinity are examples of how dangerous it is for us to deny the irrational, free side of our own nature. It reminds me of the story of Theseus's son Hippolytus, and how he incurred Aphrodite's wrath by devoting himself wholly to Artemis and denying the power of passionate love. Like the Minyads, and like pious King Pentheus, Hippolytus was fundamentally good and chaste, but that didn't save him. Quite the contrary: it was an excess of virtue that led to doom in all three of these stories, a grim reminder of the "nothing in excess" philosophy of the ancient Greeks.

The story about Ikarios also has similarities to the stories of Pentheus and the Minyads, but it gives us hope by letting us know that once you believe in Dionysus he is a good and protecting god who cares for his followers. If only Hippolytus had been so lucky with his patron, Artemis!

The relationship between women and Dionysus is best described in Euripides'

Bacchae, the story of Pentheus's downfall, which is printed in entirety in our textbook

at the end of Chapter 17. If you are really interested in women's affinity with this god and

you want to look at a serious scholarly treatment, see Dionysiac Heroines, a chapter

in Deborah Lyons' Gender and Immortality: Heroines in Ancient Greek Myth and Cult

(Princeton University Press, 1996). Princeton UP has obligingly posted several chapters of

this book on line and made them available for public access. Don't worry--the Greek verse at the top

of the page is only an epigraph. If you scroll down a little you'll get to the book itself, which is in English.

During the festivals there was a parade, as depicted here by Sir Lawrence

Alma Tadema in "A Dedication to Bacchus" (Large

Image). The believers used to wear clothing

that would make them resemble Dionysus's companions: masks and animal skin and leather

clothing. They would lead with his symbols, the vine, wine, kids, figs, and the

phallus to represent fertility. The worshippers sometimes wore twigs as decoration,

which are associated with him like the ivy but which can't have been nearly so comfortable

to wear.

During the festivals there was a parade, as depicted here by Sir Lawrence

Alma Tadema in "A Dedication to Bacchus" (Large

Image). The believers used to wear clothing

that would make them resemble Dionysus's companions: masks and animal skin and leather

clothing. They would lead with his symbols, the vine, wine, kids, figs, and the

phallus to represent fertility. The worshippers sometimes wore twigs as decoration,

which are associated with him like the ivy but which can't have been nearly so comfortable

to wear. The Dionysian celebrations (Bacchanalia, Dionysia) had different schedules around Greece. Some of the uniqueness was created by each city celebrating at her special time, thus commemorating her own acceptance of the god.

These celebrations were often associated with the theater. Aristotle claims in his Poetics that in its infancy, theater was in fact a kind of Bacchic celebration that evolved from people wearing goat skins calling themselves "tragoi" (goats, an animal sacred to Dionysus) and singing special hymns called dithyrambs. Our word "tragedy" is an Anglicized version of the Greek word, tragoidia. More on the origins of Greek theater is available from a multi-page site provided by PBS (to get all the pages, keep clicking on the tiny arrows at the bottom of the screen).

To read more about Dionysus, click here for Carlos Parada's overview of myths about Dionysus (here referred to, for some mysterious reason, as "Dionysus 2"--who was Dionysus 1???) in capsule form. You can also find more information from this on-line article on Dionysus: Myth and Ritual in Sources of the Archaic Period from the University of Haifa. Finally, you might want to look at the relatively brief account of Dionysus's birth as described by Ovid, who does an interesting job of tying in Hera's (or Juno's) wrath about Dionysus with an angry prejudice on her part against Thebes in general. (If you don't like this archaic translation, just look at Book 3 in your copy of Metamorphoses).

Return to the top of this page