Featured

Deity

AIDHS

(Hades,

King of the Dead) |

How

to identify him: It's tough. He's invisible! But if you meet him, you'll know

it. |

Roman Name: Pluto

Spouse: Persephone (Roman: Proserpina)

Sacred City: None--he doesn't get out much

Sacred Plant: Asphodel

Totem Animal: Either pure black or barren (infertile) sacrificial animals, usually sheep or cattle.

The background of the table above is

a field of asphodel flowers.

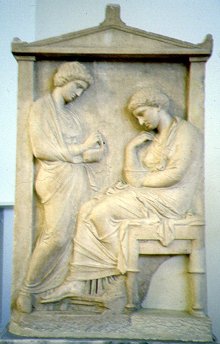

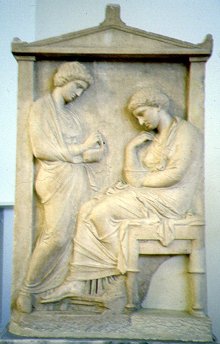

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description

of Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage,

he doesn't have an active role in any myths because usually he's too busy to leave his

kingdom. The only story that centers around him as an active participant was the occasion on

which he claimed his bride, Persephone, who is his partner in everything. Even in sculptures and

paintings you almost never see him without Persephone at his side, as in the bas relief sculpture

to the left.

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description

of Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage,

he doesn't have an active role in any myths because usually he's too busy to leave his

kingdom. The only story that centers around him as an active participant was the occasion on

which he claimed his bride, Persephone, who is his partner in everything. Even in sculptures and

paintings you almost never see him without Persephone at his side, as in the bas relief sculpture

to the left.

Notice the rooster underneath Persephone's throne. This was a common

sacrifice to the gods of the underworld or to the gods of healing. The connection

between medicine and death was very close in the ancient

world, as indicated by the two separate vials of blood from a slain monster, the Gorgon Medusa,

that Athene presented to Apollo's son Asclepius. The blood from one side was poisonous, and

the blood from the other side could be used to heal. For an interesting modern application of

this story, check out this excerpt from Bill Hayes' "Personal and Natural History of Blood," Five Quarts.

You have to move through a few paragraphs and scroll down the page a bit before you get to the bit about Asclepius.

This close connection between death and healing might be why the famous philosopher

Socrates' very last words after he drank his potion of the poison hemlock were

to remind his friend Crito to offer up to Asclepius the rooster that would no

longer be needed to awaken him in the morning: "Crito, we owe Asclepius a cock,

pay it and do not neglect it." It's almost as if he found death a welcome end

to a painful disease--in his case, not a physical disease but the mental anguish

of watching his beloved Athens fall into chaotic decline in the wake of the disastrous

Peloponnesian War. The Greek word for medicine or drug, pharmakos, was

also the word for poison.

Hades' wife is far more active than he. Even in Homer's Odyssey, when the hero

Odysseus descends to the underworld and has some unpleasant experiences there,

he claims repeatedly that it's Persephone, not Hades, who is tormenting

him. Hades himself is just a little too scary to be mentioned out loud (note that Jim Henson

picked up on this in Hades' creepy speech in the Orpheus video shown in class on September 9).

Therefore a number of euphemisms have sprung up around his name, such as

Polydegmôn ("receiver of many") and Polyxenos ("host to many," as he is

repeatedly called in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter). Sometimes Hades was called Zeus

Katachthonius, or "the underground Zeus."

Hades misunderstood

It might be easier to understand Hades' role if you think of him in terms of that last-mentioned

title. Just as Zeus is the keeper of order among

the living, Hades is the keeper of order among the dead. He is not death itself--the

Greeks had a separate god for that, named Thanatos--but rather the ruler

over departed souls. As Helios pointed out to Demeter in the Persephone video, this

makes him in a way the most powerful king possible--perhaps more so even than

Zeus--since the dead outnumber the living and thus Hades has far more subjects than his brother.

He is extremely fair and just, so much so that he is unbending,

unforgiving, and utterly inflexible. He's not an evil individual by any means,

but he's sort of like that irritating person at work who always quotes from the

rule book and refuses to deviate an inch from standard procedure. You know they're

right, at least technically, but that doesn't make it easier to accept.

Here's another common misunderstanding:

in fact, Hades' realm does not have exactly the same name as its ruler in the

original Greek, though it's frequently translated that way. Greek is an inflected

language, which means a word takes on different endings to indicate its grammatical

function. When his name is used to refer to the underworld, it is invariably used

in the possessive--Hades' or of Hades. So the phrase Go to Hades'

would have the same grammatical structure as Eat at Joe's. The underworld

is named after its ruler in the same way that Joe's is named after its owner.

You don't call the restaurant Joe, and an ancient Greek didn't call the underworld

Hades.

Contrary to what Chapter 9 in our textbook might seem to imply, the Lord of the Underworld

wasn't all bad or scary. As Pluton, Hades is the god of wealth--and

indeed, the materialistic Romans took "Pluto" as his given name. This is because

of his underground home, the source of mineral wealth in the form of gold and

gems and agricultural wealth in the form of crops (which explains his relationship

with Persephone).

You can't take it with you... but the living can't keep it, either

Valuable weapons and jewelry were frequently buried with a corpse in order

to keep its ghost at rest and prove the survivors were not receiving too much

benefit from a relative's death. It was also common for wealthy women's grave

markers, like the one on the right, to portray the deceased's jewelry box. The

box is usually held by a slave as the mistress chooses her favorite ornament.

Men who died in battle were usually portrayed in full armor, with their weapons

at rest beside them. Virtually everyone, including the poor, would be buried with

pottery items--which, as you might imagine, is a real boon for archaeologists.

This is not an indicator of the belief that "you can take it with you."

It's quite the opposite. There is a significant difference between the gloomy

classical idea of the afterlife and that of their more optimistic neighbors, the

Egyptians, who enjoyed their

time on earth so much they couldn't conceive of an eternity that wouldn't be similar

to their everyday lives. Egyptian tombs were packed full of grave goods because

they believed that their dearly departed might need them in the next world.

Greek and Roman tombs were packed with the same to keep a jealous ghost from haunting

the survivors.

For the same reason, noisy and extravagant mourning was

considered appropriate. If you were worried that your own family wouldn't be able

to put on a noisy enough show, you could always hire professional mourners who

were guaranteed to scare off any errant ghosts who hadn't yet found their way

to their final destination. Given the pessimistic view of the afterlife that prevailed in

the classical world, it's no surprise that they weren't in a particular hurry to get there.

Hungry ghosts

Ghosts were also supposed to roam the earth on

moonless nights, which is why Hades is closely associated with the goddess

Hecatê.

You may recall that according to the Homeric Hymn to Demeter it was she who told Demeter

she had overheard Persephone's abduction, as opposed to the nymph Arethusa in

Ovid's Roman version or Helios in the British video version we looked at.

Hecatê was a goddess of boundaries and crossroads and the dark of the moon;

the Romans associated her with the more terrifying side of wild, untameable Diana

(the Roman version of Apollo's twin sister, Artemis).

|

Lemur from Madagascar

The Romans also had a name for ghosts, lemures. I know that sounds funny

today--we can't help thinking of those odd little creatures from Madagascar--but the

Roman name came first. The animals were given the name by classically-educated

explorers because of their nocturnal habits, eerie silence, and bug-eyed appearance...

not to mention the fact that the local folk tradition claimed that they housed the souls of

the dead.

One way of keeping a ghost from walking was to pin its feet together, as was sometimes

done with abandoned infants. Oedipus, the hero of Sophocles' play Oedipus the King,

suffered this fate as a baby and was maimed for life as a result. The name "Oedipus" is a pun

that reflects on Oedipus's nature ("know-it-all") and on his physical characteristics ("twisted foot").

The topography of Hades' realm

Accounts vary about where Hades' kingdom is located.

In some cases it's under the earth, and in others, such as in the Odyssey,

it's at the western edge of the world, in the land of the Cimmerians. The Cimmerians

were a real people who lived near the Black Sea--north of Medea's home in Colchis.

If you don't know who Medea is, you will by the time you're done with this class.

It's not Medea herself, but her aunt, the witch Circe, who gives Odysseus directions

on how to get to the underworld. Both Medea and Circe are described repeatedly

in mythology as devotees of Hecatê, sort of in the same way that aggressive,

independent women were often branded as witches in colonial America. For more

information on this subject, listen to Vandiver's Lecture 21.

Archaeological evidence seems to point to a possible connection

between the entrance used by Odysseus and a subterranean temple complex perched

above the Acheron River in northwestern Greece. Yes, the Acheron is a real river. It's the

one that is usually seen as the outside boundary of the underworld. Its name means

"sorrowful." The other three rivers associated with Hades' kingdom, the Styx ("hateful"),

Pyriphlegathon ("flaming with fire"), and Lethe (river of forgetfulness, from which our word

"lethal" is derived), are wholly mythical.

Perhaps one of the reasons the Styx is so hateful is that awkward fact that it's the

river the gods swear by when they need to make a particularly binding oath. Once they've

sworn by the Styx, they cannot go back on their word or even use their typical trick of trying to

weasel around it. Unlike the unswerving Hades, most of the Greek gods are not

scrupulously fair and just: quite the opposite, in fact... which perhaps makes them seem more

human and less creepy!

Traditionally, spirits drink from Lethe on their way to the underworld so they will be able to bear

the loss of their life above ground, as we saw when the Styx's ferryman, Charon, offered the drink

to Eurydice in Jim Henson's Orpheus video. Plato changes this a bit in the "Myth of Er" in his

Republic (see page 300 of H&P's Classical Mythology and Vandiver's lecture 8),

where he introduces the idea of reincarnation and claims that the souls drink to forget their

previous life and begin afresh. Homer, writing some four centuries before Plato, doesn't mention

Lethe at all. As our textbook and lecture both emphasize, Homer's view of the afterlife is extremely

pessimistic. His gloomy ghosts have to continue in their shadowy existence with full knowledge of

what they have lost.

Acheron is not the only boundary. Sometimes Lake Avernus, near Naples, is described as a

portal to the underworld. This Italian alternative, of course, is the route that the Roman hero Aeneas

takes on his journey to Hades' kingdom. Other accounts say that there is an entrance to the

underworld through a bottomless lake at Lerna on the Peloponnese, and that that's how Dionysus, or

Bacchus, retrieved his human mother from the land of the dead. According to the 2nd-century traveler

Pausanias's description of Lerna

2.36.7,

"they say that Pluto, after carrying off, according to the story, Core, the daughter of Demeter,

descended here to his fabled kingdom underground." (Note: you will have to scroll nearly all

the way down the page or search with "Control F" to get to Lerna, but once you get there you'll

find a reference to a large statue of Demeter and a mention of the giant water-snake, the hydra,

slain by Heracles--the Greek name for Hercules--on the marsh of Lerna as one of his famous

Twelve Labors.)

Sometimes the ancient writers mention a place called Erebus, which is either

the final destination of the dead or a place that they pass through. If it's their

final destination, Tartarus is depicted as a separate area, circled by the flaming river

Pyriphlegathon, where punishment is doled out to those who offended the gods. If Erebus is

just a place they pass through, everybody winds up in Tartarus but it's divided up into better and

less desirable neighborhoods.

Sometimes the ancient writers mention a place called Erebus, which is either

the final destination of the dead or a place that they pass through. If it's their

final destination, Tartarus is depicted as a separate area, circled by the flaming river

Pyriphlegathon, where punishment is doled out to those who offended the gods. If Erebus is

just a place they pass through, everybody winds up in Tartarus but it's divided up into better and

less desirable neighborhoods.

The meadows of asphodel are located either in Erebus or in Tartarus--wherever

the spirits wind up. Despite the rather pleasant name, don't confuse the asphodel

meadows with the Elysian fields. Asphodel is a ghostly-looking flowering weed (see

the photo to the right). The fields of Elysium are a riotous

paradise of every pleasant, colorful plant you can think of. The only problem is, nobody

knows exactly where these fields are.

Where are those blessed fields?

Some authors locate the Elysian fields somewhere out in the sea, on the "Islands

of the Blessed," which means we might conceivably be able to get there!

In the second century C.E., about the same time

Pausanias was writing his Description of Greece, the satirist Lucian imagined

just such a possibility in his True

History. A boatload of sailors who have been blown off-course wind up on these

islands after a number of other improbable adventures, including the Jonah-like

experience of being swallowed by a whale, which is where the page I've linked

to picks up. On the islands, the crew meets up with the deceased Homeric heroes--as

well as with Homer himself, who is busy competing (and losing!!) against Hesiod

in the all-Elysian athletic games. The ever-wandering Odysseus is bored out of

his skull and wishing he could go off on another voyage, so he smuggles out a

message to his ex-lover, the immortal sea-nymph Calypso, with the help of the

story's narrator. The late King Menelaus of Sparta runs up against a familiar

situation when his wife, Helen of Troy, runs away from him (again!) with one of

the sailors. Later the hero of the story sees the errant sailor being tortured

in Tarturus, and Helen is returned (again!) to Menelaus, so I guess you could

say it turns out okay. Except for the sailor, of course.

The Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, had a more serious take on the same

idea in his poem "Ulysses," which you can find in the back of your textbook in the

chapter on "The Persistence of Myth." The aging Ulysses--the Roman name

for Odysseus--has grown restless and wants to take one last voyage,

...for

my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western

stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs shall wash us down;

It may

be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

|

Dante and Virgil in trouble

(Eugene Delacroix, 1822)

Those

spirits who are not bound for Elysium or the Islands of the Blessed have

to cross a river (either Acheron or Styx) in the boat of the ferryman Charon.

According to some

sources, the Styx was a river goddess, and she was in fact Charon's mother as well as his

workplace. One mythographer, the so-called "Pseudo-Apollodorus," claimed that Styx was

also the mother of Persephone ( ! ! ).

To pay the ferryman, a person would be buried with coins under his or her tongue.

Without that fare, the spirit would suffer the same fate as those who were improperly

buried and would be required to wander aimlessly on the far bank of the river

for a hundred years. The idea of the wandering of improperly buried souls is very

important to keep in mind if you are to fully understand the significance of Sophocles'

famous tragedy Antigone, where the young princess of Thebes, Oedipus's

daughter, risks (and ultimately sacrifices) her life for the sake of burying her brother.

According to some sources, Charon's boat is made out of horses' hooves, the only

material that can resist destruction in the corrosive waters of the Styx. Horses' hooves

are a very light substance, but then an insubstantial spirit doesn't weigh much.

In Virgil's Aeneid, the human bodies of Aeneas and his guide nearly sink

the boat, and the same thing almost happens again in Dante's Inferno when

Dante and Virgil climb on board.

The planet Pluto's solitary moon is named Charon. Even though this satellite wasn't

discovered until 1978, and Pluto has now been demoted to the status of "dwarf planet"

(mythologically enough, the asteroid Ceres was promoted to the same status at the same time, which gave

Pluto's mother-in-law equal status at last), the tradition of giving mythological names

to newly discovered orbiting objects continues. Luckily it seems like most of the new moons

are discovered around Jupiter, which makes it easier on those doing the naming--seems

like no matter how many of them accumulate, there's always one more lover who hasn't

been honored with a moon yet!

The most thorough description of Hades' realm is given

by Virgil, which is not really surprising. The Aeneid, like Apollonius's

Argonautica, is primarily a literary epic that was written by the author

rather than an old-fashioned oral epic composed on the fly, like Homer's works.

Because of this distinction, such poems tend to be a little more elaborate.

To get a sense of the physical layout of Hades' realm, check out Carlos Parada's map of the underworld, which charts the progress of both Odysseus

and Aeneas. Don't miss the text below the map, which is very useful. Parada also offers an

exhaustive annotated and illustrated

rundown on the underworld and afterlife. If that doesn't answer any lingering

questions you might have, I'd be really surprised!

Return to the top of this page

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description

of Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage,

he doesn't have an active role in any myths because usually he's too busy to leave his

kingdom. The only story that centers around him as an active participant was the occasion on

which he claimed his bride, Persephone, who is his partner in everything. Even in sculptures and

paintings you almost never see him without Persephone at his side, as in the bas relief sculpture

to the left.

The name "Hades" means "invisible" or "unseen," which is a pretty good description

of Hades' place in the mythological record. Except for the story of his marriage,

he doesn't have an active role in any myths because usually he's too busy to leave his

kingdom. The only story that centers around him as an active participant was the occasion on

which he claimed his bride, Persephone, who is his partner in everything. Even in sculptures and

paintings you almost never see him without Persephone at his side, as in the bas relief sculpture

to the left.

Sometimes the ancient writers mention a place called Erebus, which is either

the final destination of the dead or a place that they pass through. If it's their

final destination, Tartarus is depicted as a separate area, circled by the flaming river

Pyriphlegathon, where punishment is doled out to those who offended the gods. If Erebus is

just a place they pass through, everybody winds up in Tartarus but it's divided up into better and

less desirable neighborhoods.

Sometimes the ancient writers mention a place called Erebus, which is either

the final destination of the dead or a place that they pass through. If it's their

final destination, Tartarus is depicted as a separate area, circled by the flaming river

Pyriphlegathon, where punishment is doled out to those who offended the gods. If Erebus is

just a place they pass through, everybody winds up in Tartarus but it's divided up into better and

less desirable neighborhoods.