|

|

Roman Name: Juno Spouse: Zeus (Roman: Jupiter) Sacred Region: Argos (in the Peloponnese), Carthage (in North Africa), Island of Samos Totem Animals: Peacocks and Cows Sacred Plant: Lily How to Identify Her: Crown or diadem on head |

During the classical period,

ox-eyed, white-armed Hera, or her Roman counterpart Juno, was primarily worshipped as the protector of marriage.

She's a very old goddess whose name probably goes back to pre-Hellenic times (unlike her

husband Zeus, whose name is quite Greek and is a form of the generic Greek word for "god").

Some scholars have suggested that Hera could be a feminine form of hero,

designating a great and powerful lady--an interesting idea, given the fact that other scholars

have asserted there is no such

thing as a female hero in the Hellenic tradition. The "ox-eyed" goddess's association with cattle might also

indicate a connection with bull worship in the Minoan period, a time in Greek history when

the matriarchal "great goddess" was (maybe) an important figure. Or it could indicate a prehistoric function

as a mother goddess who was responsible for the fertility of cattle and crops. Then again, perhaps this

is simply one of those cases one hears about where people start to look like their favorite pets.

During the classical period,

ox-eyed, white-armed Hera, or her Roman counterpart Juno, was primarily worshipped as the protector of marriage.

She's a very old goddess whose name probably goes back to pre-Hellenic times (unlike her

husband Zeus, whose name is quite Greek and is a form of the generic Greek word for "god").

Some scholars have suggested that Hera could be a feminine form of hero,

designating a great and powerful lady--an interesting idea, given the fact that other scholars

have asserted there is no such

thing as a female hero in the Hellenic tradition. The "ox-eyed" goddess's association with cattle might also

indicate a connection with bull worship in the Minoan period, a time in Greek history when

the matriarchal "great goddess" was (maybe) an important figure. Or it could indicate a prehistoric function

as a mother goddess who was responsible for the fertility of cattle and crops. Then again, perhaps this

is simply one of those cases one hears about where people start to look like their favorite pets.

Another possible indication of a fertility goddess role in her past is the fact that she is associated with the Milky Way. Our word galaxy comes from the Greek gala, or milk (you may recall that the ivory statue created by the sculptor Pygmalion and brought to life by Aphrodite was named Galatea, a reference to her very white skin... which, of course, an ivory statue would have). The story on pages 314-315 of Harris & Platzner's Classical Mythology recounts how the Milky Way was formed from the milk of Hera's breasts, though a variant version of the Milky Way etiology is offered in the story of Phaeton featured in the same chapter. Color Plate 3 is a painting of the incident by the Renaissance artist Jacopo Tintoretto. According to other sources, some of the milk drops fell to the ground and became lilies, Hera's sacred flower.

Some commentators have pointed out that lilies' physical resemblance to female genitalia are yet another indicator of a fertility dimension to Hera's nature. Unlike her sister Demeter, who is associated almost entirely with the fertility of crops, when we talk about Hera and fertility we are usually talking about sexual reproduction. Also unlike Demeter, Hera is more interested in the sexual relationship than in the outcome--the sacredness of marriage is emphasized rather than the sacred tie between parent and child.

Although she doesn't always come off well in mythological accounts, in religious practice Hera was one of the most respected and revered of the goddesses. She is generally shown as being extremely stately and dignified, as in the vase paintings above. She never seems to lose the royal aura that is hers by right as the Queen of Heaven. You will often see her wearing a veil, both to emphasize her mystery and to emphasize her role as a married woman.

It might seem strange that cattle are sacred to Hera when you consider her persecution of poor Io, but remember that Zeus turned Io into a cow in order to fool her. One can understand his reasoning and his hope that turning Io into Hera's favorite animal might avert her anger. Unfortunately, it didn't work out that way.

The plus side of the whole Io incident for Hera was that it gave her

a favorite bird, as a result of the story of her faithful servant Argus (don't confuse

Argus with Argos, which is her favorite region. In Greek, these two names are

spelled the same, but apparently that didn't confuse anybody). The Argus

legend has hung on in our culture in an unexpected way, as you'll see if you check the yellow pages

in many a big city phone book: Argus is one of the most popular names for detective agencies and

security systems companies. So the adversarial relationship between Argus and Hermes, protector

of thieves, continues even today. You may recall that a commonly used epithet, or nickname,

for Hermes is Argeiphontes, or Argus-killer.

The plus side of the whole Io incident for Hera was that it gave her

a favorite bird, as a result of the story of her faithful servant Argus (don't confuse

Argus with Argos, which is her favorite region. In Greek, these two names are

spelled the same, but apparently that didn't confuse anybody). The Argus

legend has hung on in our culture in an unexpected way, as you'll see if you check the yellow pages

in many a big city phone book: Argus is one of the most popular names for detective agencies and

security systems companies. So the adversarial relationship between Argus and Hermes, protector

of thieves, continues even today. You may recall that a commonly used epithet, or nickname,

for Hermes is Argeiphontes, or Argus-killer.

The peacock, like Hera herself, has two sides to its nature. It is stately and beautiful, but it has an extremely shrill voice that resembles the shrewish character that Hera shows in so many of the myths. It also has a dimension of pride to it, and in the mythology it does seem that it's always a blow to her pride that gets Hera into trouble. As examples, consider the golden apple incident that kicked off the Trojan War and the many stories of Hera's endless pursuit of the women who receive Zeus's amorous attentions.

And it wasn't just women. Although she was plenty angry about the golden apple thing--and she continued her enmity against all the Trojans throughout the ten long years of the Trojan War--Hera was already angry with Troy because in a previous generation Zeus had become enamored of the young Trojan prince, Ganymede, and brought him back to Olympus. Ganymede became the royal cupbearer to the gods when they drank their nectar, an important role that until his appearance on the scene had been fulfilled by Hermes or Hebe, the daughter of Hera and Zeus.

One of these unfortunate women whom we haven't yet encountered was Aegina (pronounced EGG-in-uh, believe it or not), the daughter of a river god named Asopus. She bore Zeus a son named Aeacus, who was to become the father of Peleus, who was the father of Achilles. Aeacus's other son, Telemon, fathered the hero Ajax, who fought with Achilles at Troy.

To seduce Aegina, Zeus did his usual shape-changing trick and turned himself into either an eagle or a flame, depending on which account you read. He bore the maiden off to a large island in the Saronic Gulf that still bears her name (today it's famous for a beautifully preserved temple to Aphaia--a local deity--and a brisk trade in high-quality pistachio nuts). Aegina's father was furious and searched everywhere for her until he finally ran across Sisyphus, the King of Corinth, who had witnessed the abduction and reported how he had seen the god carry off the hapless maiden (sound familiar?). When Asopus came to collect his daughter, Zeus drove him off with his thunderbolts. Sisyphus's fate was rather worse, as we saw when we visited the underworld: he was condemned for all eternity to roll a huge rock up a steep slope in Tartarus. Every time he almost gets to the top, the rock slips from his grasp and he has to start all over again.

Hera was so angry about this latest escapade she wiped out almost all of the population of Aegina--which is a pretty large island, so that's a lot of people. The only way the place could be repopulated was by turning the local ants into human beings, so Aeacus--and after him, his grandson Achilles--became Ruler of the Ant People. Sounds like a B-grade horror movie, doesn't it? According to some accounts Hera destroyed the people of Aegina with a plague, but according to others she sent a dragon to do the dirty work. I prefer the dragon account because it has such interesting parallels with the middle eastern myths about serpents and dragons that are associated with the feminine principle. The plague story, however, is the more popular version.

|

Our textbook tells us that these parents were Oceanus (or "Ocean," as he's called in our translation of Prometheus Bound), the primoridial ocean, and Tethys, the world's more powerful river goddess. The ancient writer Pausanias claims that Hera was raised by much humbler river nymphs, one of whom was named Euboea. This name, pronounced "Evia," was adopted by some of the earliest producers of bottled water, Evian Water. Both versions of Hera's childhood are "correct": it depends on which sources you consult.

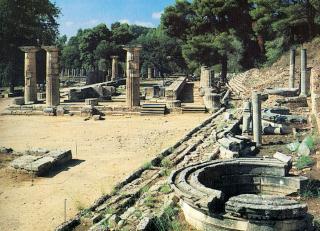

The river nymph story claims that the young goddess was brought up near Argos, which is an appropriate home for her and for nature deities of all kinds because it's a very fertile part of Greece. Later Argos would become the site of her most important temple, the Heraion (or Heraeum, as it's sometimes spelled), which is pictured above. It was described in gorgeous detail by Pausanias, who visited in the second century A.D.

Not everyone subscribes to the "love at first sight and waiting for maturity" report about Zeus (sounds like Theseus and Helen, doesn't it?). It's true that Zeus does have a history of falling in love on sight, but one thing he does not have a history of is delayed gratification, and the fact is that in none of the versions does he marry or seduce Hera at once. A more cynical theory is that all the "good stuff" had already been apportioned out to other deities by the time Hera emerged from Cronus, and there was nothing left over for Hera, so Zeus was planning to offer her the Queen of Heaven job as a sort of consolation prize.

Whatever the case, whether he loved her or whether he just wanted to absolve himself of guilt, Hera refused to go along with her brother's plans and she flatly turned down his proposal of marriage. Never one to take no for an answer, Zeus...

...can you guess what he did next?

If you said "I'll bet he changed his shape," you're right. Maybe he does use the same old trick over and over, but you've got to admit it's effective. As Sappho's contemporary, the Archaic Greek poet Arkhilokhos (7th century B.C.E.) says, "The fox knows lots of tricks, the hedgehog only one: but it's a winner."

In this case, Zeus conjured up a rainstorm near a mountain in Argos where Hera liked to walk, and turned himself into a cuckoo (don't say it. I swear I'm not making this up). After getting thoroughly wet and bedraggled, he turned off the rain and waited. When Hera came along, she sat down for a moment to enjoy the fresh air and rest her feet, and Zeus took the opportunity to crawl into her lap. The sodden bird awakened her sympathy and she kissed it and snuggled it against her breast and... well, the rest is history. On the site where she sat down the Argives dedicated a temple to Hera Teleia, which means "Hera fulfilled." "Teleia" also means "concluded" or "finished," but presumably that's not what the Argives meant! Anyway, she became the marriage goddess then and there.

Hera had four children:

Because of the unnatural nature of their birth and Hera's anger at the time, neither son was quite right: Hephaestus had a beautiful soul but a hideous body, while Ares looked glamorous on the outside but was twisted and sick on the inside...which, I've always felt, is an awfully good description of exactly what war is like. The potential benefits of making war can be extremely seductive until you start experiencing the losses.

Occasionally a fifth child will be mentioned who is wholly monster: Typhon, the dreadful creature created out of sheer vengefulness. He was mentioned in Hesiod and we will encounter him again in the Hymn to Pythian Apollo.

However he may talk about her behind her back, Zeus is still susceptible to Hera's charms and

he falls for her repeatedly. Not only is there the famous episode from the Iliad

where Hera borrows Aphrodite's enchanted girdle to seduce him--see page 186 in Harris and

Platzner--but there's also the case of her annual bath in

Kanathos, a sort of spa treatment that renews her virginity and makes Zeus crazy for

her all over again. Here she is on the Parthenon frieze, flirting with him from beneath her

veil. Yow!

However he may talk about her behind her back, Zeus is still susceptible to Hera's charms and

he falls for her repeatedly. Not only is there the famous episode from the Iliad

where Hera borrows Aphrodite's enchanted girdle to seduce him--see page 186 in Harris and

Platzner--but there's also the case of her annual bath in

Kanathos, a sort of spa treatment that renews her virginity and makes Zeus crazy for

her all over again. Here she is on the Parthenon frieze, flirting with him from beneath her

veil. Yow!

Because of this interesting ability of hers to repeat the life cycle, Hera was worshipped in three different guises: Hera Parthenos, or maiden, in the spring; Hera Teleia in the summer and autumn; and Hera Chera, or Hera the widow, in the winter (one assumes this is "widow" in the same way we talk about a "football widow" or "golf widow" whose spouse goes missing every weekend--though in Zeus's case he's usually playing the field as opposed to playing on a field). Hera was worshipped all over Greece, just as marriage was celebrated all over Greece, but her main sanctuaries were at Argos, the island of Samos, and the city of Sparta on the Argive plain (though Sparta was not one of Hera's "special cities"; there was an even more famous sanctuary to Artemis there). Sparta's grand temple might seem ironic in light of the fact that Greek literature's most famous adulteress, Helen of Troy, came from Sparta. Apparently Helen didn't listen very well to the local priests!

You can find more information on the Heraion at the Perseus Project, and From Myth to Mind has an extremely engaging site on her temple on Samos.

There's an interesting legend about the temple at Argos involving two brothers named Biton and Kleobis, which was recounted by the historian Herodotus in the fifth century B.C. I won't spoil the surprise by telling you what it's about--you'll have to check the link. Wow, and they call Hesiod a pessimist...

It would seem that even in this day and age, Hera has her adherents. The ultra-modern feminist poet, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), wrote a beautiful ode in honor of Hera and Hymen, the deity in charge of weddings, in 1921. And the Jungian psychiatrist Jean Shinoda Bolen, in her book entitled Goddesses in Everywoman (Harper and Row, 1984), claims that the Greek goddesses, especially Hera, are useful as archetypes in her clinical practice. She points out that a woman inspired by Hera is completely taken up in her role as wife to such an extent that other ties, even to one's children, aren't nearly as strong (she cites Nancy Reagan as a 20th-century example). In an interview, she remarks on how typical it is for a woman who defines herself by her marriage to strike out and blame everybody except a philandering husband... just as Hera continually zaps the innocent victims of Zeus's lust.

If the Hera side of an individual gets out of balance, the results can be gruesome. According to Bolen, Ares is a case of "'Like mother, like son'--Ares's uncontrolled fury on the battlefield mirror[s] Hera's out-of-control vindictiveness" (Goddesses in Everywoman 165). Instead, Bolen suggests that Hera could more productively model herself on her other son, Hephaestus, and try to channel her rage and aggressiveness into creative channels. But in all the myths, she notoriously shows favoritism to Ares instead. Interestingly enough, this same favoritism is not shown by her spouse: in fact, Homer's Iliad includes a speech in which Zeus admits he just doesn't like Ares. More on that when we get to Ares Week.

Medea is certainly the ultimate example of out-of-control rage inspired by Hera. Poor Hera is caught in a peculiar situation in that particular relationship: here's Jason, her favorite and her champion against her enemy Pelias, dishonoring the very thing that she represents. No wonder she inspires Medea to go to shocking lengths. Medea murders the innocent Princess of Corinth and her father, the King, in an absolutely horrendous manner because Jason wants to get a divorce and "marry up." According to Euripides, Medea even goes so far as to murder her own children just to strike out at Jason, but this was a revised version of an older myth in which these children were murdered by the Corinthians as revenge for the death of their Princess and King. Euripides simply kicked Medea's violent nature up a notch.

But whatever the case, notice that Medea never harms a hair on Jason's head. Nor does she harm Aegeus, her second husband, when he kicks her out of Athens for trying to murder Theseus. Because she defines herself primarily as a wife, the idea of completely destroying her husband would be unthinkable because that would involve destroying her own identity. Medea is truly a devotee of Hera.

To read more about Hera, click here for her entry from the Encyclopedia Mythica, and here for an overview of myths about Hera in capsule form, courtesy of Carlos Parada. Parada even offers for sale a handy color-coded table depicting "Hera's Wrath," indicating the major characters who got zapped by Hera, and why. The darned thing is so complex it looks like a royal genealogical record!

Return to the top of this page