ZEUS (Zeus)

King of the Gods |

ZEUS (Zeus)

King of the Gods |

This web page is a complement to the section on pages 135-140 of your textbook. Please read that section either right before or right after the web page. Explore all the hyperlinks below, either as they come up or after you have finished reading the page through. Clicking on a link will open a new window on your computer's browser, so you won't lose contact with this page and you can continue reading while you wait for the new pages to load. To close a window, click the little "x" way up in the upper right-hand corner.

Roman

Name: Jupiter Roman

Name: JupiterSpouse: Hera (Roman: Juno) Sacred Regions: Dodona, Olympia, Nemea Sacred Plant: Oak Totem Bird: Eagle How to Identify Him: Look for a thunderbolt, an eagle, or a throne

|

Zeus is called Jupiter in Roman mythology. You might also have heard him referred to as Jove, but that is a name that started in the Renaissance and it does not have any basis in any of the ancient languages.

|

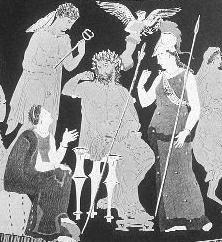

The picture to the left, a photograph of a vase painting from Attica (the area

of Greece in which Athens is located, which produced the most sophisticated pottery

during the classical period--especially the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.), shows

Zeus sitting in judgment on his throne on Mount Olympus. As king of the gods,

this was one of his most important roles. His daughter Athene, goddess

of wisdom, stands on his left hand, and the goddess Themis, representing

justice, hovers over his right shoulder. I'm not sure who the winged figure above

his head represents, though I suspect Nike, goddess of victory. The woman

seated at his feet takes a typical posture for a suppliant asking a favor. Achilles'

mother, Thetis, takes a similar pose in Book I of Homer's Iliad when she needs to make a request on behalf of her son.

The picture to the left, a photograph of a vase painting from Attica (the area

of Greece in which Athens is located, which produced the most sophisticated pottery

during the classical period--especially the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.), shows

Zeus sitting in judgment on his throne on Mount Olympus. As king of the gods,

this was one of his most important roles. His daughter Athene, goddess

of wisdom, stands on his left hand, and the goddess Themis, representing

justice, hovers over his right shoulder. I'm not sure who the winged figure above

his head represents, though I suspect Nike, goddess of victory. The woman

seated at his feet takes a typical posture for a suppliant asking a favor. Achilles'

mother, Thetis, takes a similar pose in Book I of Homer's Iliad when she needs to make a request on behalf of her son.

Since Zeus is supposed to oversee the world and make sure the universe runs reasonably well, he is generally the god that people would appeal to when life seemed generally out of balance, in the hope that he would set things right again. As one might imagine, not everybody sees eye to eye on what "right" is. Thetis's request for Achilles, for instance, was made because she thought he had been wronged by King Agamemnon--but although he gains retribution for that wrong it is at the cost of a great many Greek warriors' lives and safety. In Sophocles' tragedy Antigone, the two main characters have diametrically opposed positions, yet each claims to be following the will of Zeus.

Zeus is also the protector of the city and of hospitality, or xenia. Because there were no hotels in ancient Greece, members of the aristocracy had a system worked out where the members of one family could stay at another's home and enjoy their protection. For that reason, the word xenos meant both "stranger" and "guest," and is sometimes translated as "guest-friend." The host was expected to provide guest-gifts and to feed and house his xenoi--and the descendents of his ancestors' xenoi, since these relationships were inherited--for as long as they were in town. Anyone who violated the law of xenia by mistreating a guest ran the risk of Zeus's wrath. Likewise anyone who broke an oath. In fact, Zeus had two epithets that referred to these functions: Zeus Xenios, as protector of hospitality, and Zeus Horkios, as protector of oaths, as well as the name Zeus Hikesios, which referred to his role as protector of suppliants.

In Greece today, "Hotel Xenia" is a popular name for tourist hotels.

|

By the way, it's not just the ancients who named celestial objects after Greek mythological figures. One of the moons of the planet Jupiter--Zeus's Roman name--is named Amalthea. Another is named Metis, after the goddess that Zeus swallowed before giving birth to Athena (see page 4 of our textbook). Here are some photos, in case you want to take a look at them. There's also a moon named Leda, though it isn't pictured here. As described below, Leda was yet another of Zeus's lover, the mother of Helen of Troy and Castor and Pollux.

See also this Roman coin from the reign of Caesar Augustus, depicting Caesar on one side and Capricorn and the horn of plenty on the other. The myth continued from the Greeks on to the Romans. It would make sense that Caesar would want to be associated with the being from whom all good things flow, a cornucopia of generosity. Roman emperors were experts at using mythology to further their political purposes.

One tale that is usually consistent is the story of the aegis (see the last sentence on page 147 and the photograph of Athene on page 148 of Classical Mythology regarding the aegis as the symbol of Zeus's power), which is supposed to have been made of Amalthea's skin, preserved after her death--this, of course, is only a part of the versions of the myth where she is a goat rather than a nymph. I don't know how the snakes found their way onto the aegis, but they're always there. In the ancient world, snakes were often associated with immortality because of their trick of shedding their skin and becoming renewed.

Ironically, despite his role as keeper of the universal order, Zeus seems to be entirely incapable of keeping order in his own household. His children and siblings frequently defy him, and sometimes he seems positively overwhelmed by all the demands made upon him. And who wouldn't? The humorous vase painting below seems to capture his dilemma perfectly, as does a Renaissance painting of The Council of the Gods by the artist Peter Paul Rubens two millennia later.

Zeus's worst relationship seems to be with his sister/wife, Hera. The two were never well-suited, and their marriage was only a marriage of convenience in the first place: according to the story, after the battle with the Titans was over and Zeus and his other siblings had carved up the universe between them--with Poseidon taking the sea, Hades taking the underworld, Demeter taking the crops, and Hestia taking the hearth and home--there was nothing left over for Hera. So as a consolation prize, the newly-crowned king of the gods offered to marry her and make her the queen of heaven. Not surprisingly, she turned him down, so he had to resort to trickery in order to seduce her (more on that subject when we focus on Hera).

Hera became the guardian of marriage, which also is rather ironic, since Zeus became notorious for his many extramarital affairs. There were so many of these that you need a chart just to keep track of his more famous lovers and children. Some mythographers explain this in terms of Zeus's origins as a fertility god (as our book's editors put it on page 140, his many affairs "enrich the human gene pool with heroic stock"), but others claim that the reason for so many affairs with humans was to establish a "divine right of kings," as members of the aristocracy could claim the gods as ancestors through the lines of heroes with divine parentage. If that was the case, it backfired somewhat in the later classical period. Philosophers began to reject the idea of a womanizing deity. Socrates' suggestion that such behavior would be inappropriate for the ruler of the universe, and that the myths must therefore be allegorical rather than literal, was one of the reasons he was executed for "corrupting the youth" of Athens with such untraditional ideas.

This does not mean, as some people think, that all of the classical Greeks actually believed that the myths were literally true; what it does mean is that they were bothered by a departure from traditional religious practice. Socrates' assertion that Zeus did not have human impulses and thus did not have human needs could have interfered with the time-honored methods of sacrifices and worship. His contemporary, the comic playwright Aristophanes, pointed out in this passage of The Clouds just how topsy-turvey would be a world in which one questioned the traditions surrounding Zeus (see especially the telling line, "I never realized Zeus is gone and in his place this Vertigo's become the king"). Socrates' pupil, Plato, and Plato's pupil Aristotle, were both careful to make that distinction and to insist on the importance of worship according to custom. They learned from the example of their teacher's execution.

|

The photograph on page 141 shows Zeus striding off with Ganymede, but in this case he is depicted in human form.

Turning himself into a bird wasn't such an unusual trick for Zeus--he turned himself into a swan to seduce Leda (mother of Helen of Troy and the twins Castor and Pollux, the Dioskouri or Gemini--although they were twins, only Pollux was Zeus's son; Castor was the child of Leda's mortal husband, as was Helen's twin sister Clytemnestra). Zeus made something of a habit of turning himself into birds and animals, usually to conceal his infidelity from the ever-vigilant Hera, part of whose role as guardian of marriage was to try to prevent this sort of behavior.

No one knows why such shape-changing became part of Zeus's background, but there are a number of theories, including the idea that the god's power was supposed to manifest itself in many different elements of nature. This last idea appeals particularly to artists, both ancient and not-so-ancient, who liked to indicate his presence through his various forms or attributes; perhaps one of the best examples of just how subtle yet pervasive Zeus's presence could be is the Renaissance painter Antonio Allegri da Correggio's depiction of the courtship of Jupiter and Io, in which Zeus (Jupiter) appears as a cloud.

Zeus turned himself into a bull in order to carry off the princess Europa, and into a ray of sunlight or a shower of gold to seduce Perseus's mother Danaë, whose jealous father had locked her into a tower with only a tiny window through which the god was able to enter.

The tables were turned in the case of Io, to whom he came in the form of a man...but then he turned her into a cow in order to hide her from Hera. (Note: the Io link will take you to a list of annotated references, all hyperlinked. You don't need to follow any of the hyperlinks if you aren't interested, but do read down the list to get an idea of the story. Europa and Io are important because major geographic features were named after them, in Europa's case the continent of Europe and in Io's case both the Ionian Sea and the Bosporus strait, "bos" coming from the root word for "cow"). Because of her time in Egypt Io is often associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor.

Most of the myths that deal with Zeus are either the tales of creation and

the fights with the Titans and the giants as described in our text, or tales of

his many love affairs, or tales of his protection of mortals who respect his laws.

One of the more charming stories is the folk tale of Philemon

and Baucis (scroll down the page past Midas to get to the story).

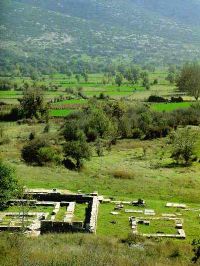

The main places associated with Zeus are Dodona, pictured to the right, and Olympia, which is a city in the southern area of Greece known as the Peloponnesus and is not to be confused with Mount Olympus, which is much further north.

Dodona was the site of Zeus's oracle, where a priest or priestess interpreted the sound of the wind rustling through the leaves of the sacred oaks. Sir James Frazer, author of the influential (if not entirely trustworthy, as Elizabeth Vandiver points out) multi-volume Victorian commentary on ancient myth entitled The Golden Bough, traced some interesting connections between Zeus's relationship with the oak and similar Celtic and Teutonic traditions.

Olympia is probably best known today for being the site of the ancient Olympic games. There were actually four famous sites for Panhellenic competitive games, which is why the Olympics took place only once every four years: the Olympic games at Olympia, the Nemean games at Nemea, the Pythian games (named for the Python, a monster slain by Apollo) at Delphi, and the Isthmian games at Isthmia (on the southeast side of the Isthmus of Corinth). The games at both Olympia and Nemea were sacred to Zeus, the Pythian games were sacred to Apollo, and the Isthmian games were sacred to Poseidon.

The famous sculptor Pheidias, who designed the Parthenon in Athens, was commissioned to create a massive gold and ivory statue of Zeus for the temple at Olympia, and the result was so spectacular it became one of the seven wonders of the world, along with the pyramids of Egypt and the hanging gardens at Babylon.

Because the Olympic games were the most prestigious, Zeus became associated with athletes. The 5th-century (B.C.) Greek poet Pindar was known for his odes that drew on stories of the gods, including Zeus, to parallel and praise the athletes who competed in the various games. The ancient travel writer/historian Pausanias, writing in the second century A.D., tells how in the Altis, the sacred grove dedicated to Zeus at Olympia, there were a number of bronze statues of Zeus that had been paid for out of the fines levied on athletes who cheated (you don't need to read the entire page here--just the first three or four paragraphs. It's a very long excerpt). I recently read an article in a news magazine that was scandalized by the "recent" upswing in Olympic athletes who cheat, and I couldn't help wondering what the author would have thought of all those statues in the Altis.

If you are interested in Olympia and would like to look at another web page with larger, clearer pictures and different text, try this one at Thinkquest. It includes maps and a really nice photograph of the arch through which the athletes would emerge into the stadium. It is a bit slow to load, so you might load it into another window and read this page as the other one comes up.