from a drawing by Field Talfourd

from a drawing by Field Talfourd |

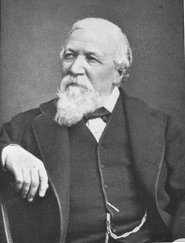

In later years, as his popularity increased, his appearance became much more that of the staid, successful Victorian sage. When this page finishes loading you can scroll down to the bottom and take a look at his appearance then. The photograph, taken when he was 69 years old and issued in three sizes by the Browning Society, shows a Victorian Literary Lion in all his glory.

He wasn't always a literary lion. During his wife's lifetime his fame was overshadowed by hers, and he was sometimes referred to as "Mrs. Browning's husband." Given the fact that Mrs. Browning's work was held in such high esteem her name had been suggested--possibly in jest, but still mentioned--for the position of Poet Laureate at William Wordsworth's death in 1850 (the Laureate position instead went to Tennyson, and to this day no woman has ever held that post), this is not as demeaning as it might sound. Still, it must have been an irksome nickname nevertheless.

Since the Browning love story and marriage is such a famous subject I'm not going to write yet another account of it; if you don't know what I'm talking about you can find the major details here. If you're a snoop or a romantic, check out this copy of the famous love letter from Robert to Elizabeth: it was posted on line on Valentine's Day a couple of years ago as part of an exhibit of "the 10 best love letters across the centuries" (no, he didn't burn it after all).

Browning's first published poem, Pauline, a Fragment of a Confession (1833), was heavily influenced by Shelley's concept of the poet as a highly sensitive being whose beautiful soul dwells apart from the rest of mankind, communing only with nature and with itself in a sort of Platonic realm. The poem contains a long passage of tribute that refers to Shelley as a "Sun-treader" (line 151) and claims that "one so pure as thou/Could never die" (208-209). Pauline, however, died relatively quickly; not a single copy was sold, and it was ignored by many reviewers--except John Stuart Mill, who in an otherwise relatively positive review claimed that the poem exhibited "a more intense and morbid state of self-consciousness than I ever knew in any sane being." The Literary Gazette of March 23, 1833, didn't pull any punches at all, calling Pauline "Somewhat mystical, somewhat poetical, somewhat sensual, and not a little unintelligible, -- this is a dreamy volume, without an object, and unfit for publication."

Clearly this kind of work was not what the public was looking for. Browning drew into himself to create a new style of poetry, more functional and less personal. He developed an idea of the poet as what he called a "maker-see"; that is, an artist whose function is to help us see clearly aspects of the world that we might neglect otherwise. This function applies to all artists of all types, as he says through the voice of the painter who is the subject of "Fra Lippo Lippi" (c. 1853):

|

...we're made so that we love First when we see them painted, things we have passed Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see; And so they are better, painted--better to us, Which is the same thing. Art was given for that... |

| (300-304) |

What he would become famous for was his brilliant portrayal of human psychology, with glimpses inside the mental processes of a vast number of different characters--even some unbalanced mental processes, as best illustrated in a publication entitled, appropriately, Madhouse Cells (1842). The best-known of the two poems it contained is "Porphyria's Lover," in which the narrator explains ingenuously that he strangled his girlfriend because actually he knew she wanted him to, and then remarks that at this very moment he is sitting with her "smiling rosy little head" cozily propped on his shoulder.

Yet Browning never lost his fascination with Shelley's subjective introspection, and in fact the only prose work of criticism he ever published was an introductory essay to a new edition of Shelley's letters that came out in 1852. In one of my favorite poems, "Memorabilia" (written c. 1851 and published in 1855), he describes how astounded he was upon meeting a stranger in a London bookstore who had actually met his idol face to face. Shelley died in 1822, when Browning was ten years old, so he had never had that opportunity himself. Naturally, he felt that this should have been a high point, if not a life-changing, earth-shattering moment. The stranger was less impressed, and when Browning turned pale and stared at him he was graceless enough to laugh out loud.

|

Ah, did you once see Shelley plain, |

Those last two stanzas are a brilliantly phrased put-down. By comparing the man's life to a barren moor with only one bright spot--not only a feather, but an eagle's feather, the one bird that according to legend is able to look directly at the sun without being blinded--Browning implies that anybody who can't appreciate a sublime experience when it offers itself is a person completely devoid of imagination and interest. What's more, that one sublime moment is discarded, like the eagle's feather, and left lying on the ground until someone comes along who knows its value. This man has "a certain use in the world no doubt," but has no understanding of anything outside of his own tiny, circumscribed world...a world that Browning has no use for and describes as ultimately forgettable.

Official photo taken for the Browning Society (Yes! There was one!) |

In his mature years, Browning mostly affected to scorn poetry that revealed too much about the poet--the very opposite of the reflective Shelleyian style that he had adopted in Pauline. Instead, the poet should maintain an amoral and nonjudgmental distance from his subject, closer to the Romantic poet John Keats's concept of a "chameleon poet" who is able to immerse his own personality in those of the characters he writes about.

Browning described such self-revelation as something that is almost obscene, like a house whose front has been sheared away by an earthquake to give a dollhouse-like view open to the prying eyes of the vulgar and curious:

|

Do I live in a house you would like to see? Is it scant of gear, has it store of pelf? [money] "Unlock my heart with a sonnet key?"

Invite the world, as my betters have done?

"For a ticket, apply to the Publisher."

I have mixed with a crowd and heard free talk

The whole of the frontage shaven sheer,

The owner? Oh, he had been crushed, no doubt!

"I doubt if he bathed before he dressed.

Friends, the goodman of the house at least

Outside should suffice for evidence:

"Hoity toity! A street to explore, |

| (1876) |

The quotation in italics (Browning's italics; I haven't added anything) is from William Wordsworth's poem "Scorn not the sonnet," although Browning added the word "same." The "sonnet key" idea seems to have irked him a bit, since the same line is paraphrased at the beginning of this poem, as well as here at the end. James F. Loucks, editor of the Norton Critical Edition of Robert Browning's poetry, suggests that what really irked Browning was the recent publication of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sonnet sequence, The House of Life, which had an extremely sensuous and confessional tone, inspiring one critic to christen the work of Rossetti and his fellow Pre-Raphaelites "The Fleshly School of Poetry."

So how do you get away from excessively personal poetry? You can get dramatic. Shakespeare wrote plays; Browning adapted an emerging form known as the dramatic monologue. It became the form for which he was most famous, and he is generally considered the master of dramatic monologues. I'll explain more about what these are and how they work, as opposed to full-blown drama, but first I'd like to give you a little background about Browning's best-known dramatic monologue, "My Last Duchess." Please click here to proceed with the on-line lecture.

Looking for a Browning-themed vacation? You can rent the Brownings' apartment in Florence, or if you prefer to stay in the United States you might want to visit the Armstrong Browning Collection, located at Baylor University in Waco, Texas and housing "the largest collection of Browningiana in the world."